Pete Seeger

Even if everyone didn’t admit it, we all knew that he

[Dylan] was the most talented of us.

Dave Van Ronk

where “nobody liked rock ‘n’ roll, blues or country” and

where “you couldn’t be a rebel—it was too cold.”

Bob Dylan

“In those days, artistic success was not dollar-driven; it

was about having something to say.

Bob Neuwith

“If the time becomes slothful and heavy, he [the poet] knows

how to arouse it... he can make every word he speaks draw blood. Whatever

stagnates in the flat of custom or obedience or legislation, he never

stagnates. Obedience does not master him; he masters it. The attitude of great

poets is to cheer up enslaved people and horrify despots. The turn of their

necks, the sound of their feet, the motions of their wrists, are full of hazard

to the one and hope to the other.”

Walt Whitman

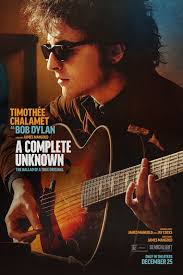

Having sat through numerous Bob Dylan documentaries and

films of varying quality, including spending eight hours watching Renaldo and

Clara, I think it qualifies me to review this latest film about the life of Bob

Dylan. A Complete Unknown was the subject of a barrage of publicity, both on

television talk shows and in social media. It is well-acted, with Timothée

Chalamet’s performance as Dylan especially noteworthy in its remarkably

accurate impersonation of Dylan’s singing and speaking voice. It is visually

stunning and audacious in its authenticity, but it is ultimately a triumph of

style over substance. Despite some excellent performances, each actor had to

learn the instrument and voice of their character, which they did remarkably

well. The performances, however, remain at the level of skilful impersonation,

rather than a profound understanding of the different personalities.

The story traces Dylan's early entry into New York City in

early 1961, up until 1964 when he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. Trying

to cram into two hours four years of the life of such a critical musician

naturally will bring about “evasions and elisions”.

As Richard Broody writes “The details that get sheared off

matter, not least because they embody the spirit of the age: how a young

musician without a day job finds a place to live in the Village is even more of

an emblem of the times than the overwrought precision of the movie’s costumes,

hair styles, and simulacra of street life. Without the anchor of material

reality, the life of the artist is reduced to a just-so story of soaring above

banalities and complications—one that parses easily into its few dramatic

through lines as if the stars were aligned from the start. What’s lost is the

way a colossal spirit such as Dylan confronts everyday challenges with a

heightened sense of style and daring.”[1]

The film is a fictional account of Dylan's early career,

loosely based on Elijah Wald's book, Dylan Goes Electric!, as well as on James Mangold's

conversations with Dylan. It appears that little to no research has been

conducted at the Bob Dylan archive.[2]

The director Mangold said that the film is "not a Wikipedia entry", and

that he did not "feel a fealty to a documentary level of facts".Mangold’s

film does little to examine the political and ideological intricacies of the

time. There is no “coherent theory” of the time; it often relies on clichés to

move the film along. Mangold’s attempt to portray the events of 1962 through

news broadcasts is clumsy and borders on the melodramatic, which forces him to

invent things that did not happen.

Mangold spends a significant amount of time in the film

examining Dylan’s relationship with Pete Seeger. Alongside Woody Guthrie,

Seeger was a considerable influence on the young Dylan. Seeger quickly

recognised that Dylan was unlike anything or anyone that had gone before,

saying, “I always knew that sooner or later there would come somebody like

Woody Guthrie who could make a great song every week. Dylan certainly had a

social agenda, but he was such a good poet that most of his attempts were head

and shoulders above things that I and others were trying to do.”

According to Wald Seeger and his followers “believed they

were working for the good of humanity … but were intensely aware of the forces

marshalled against them: the capitalist system and the moneyed interests that

upheld it” Seeger was sentenced to one year 1961 for contempt of Congress when

he refuses to name names of associates with connections to the Communist Party.

Seeger, “I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my

philosophical or religious beliefs, or my political beliefs, or how I voted in

any election, or any of these private affairs.”

The early Dylan was like a musical sponge. As the writer

Paul Bond noted, “Dylan was listening to all sorts of music—country, the blues

of Muddy Waters, and, eventually, folk. The latter, which had grown in part out

of ethnomusicological research into traditional songs as “music of the people,”

had been promoted by the Stalinist Communist Party and other left circles as a

means of tackling contemporary issues and espousing a broadly progressive

political outlook in popular song. In contrast to the banality of such

contemporary songs as “How Much Is That Doggy In The Window. At the same time,

the American folk scene offered a wide range of performance models, accepting

the high-art theatricality of a John Jacob Niles alongside Guthrie's more

“home-spun” performances. In the American scene, there was not the same

emphasis on formal “authenticity” as there was to be in the English folk

revival. Alongside the content of the music, therefore (“Folk music delivered

something I felt about life, people, institutions and ideology”), Dylan was

also receptive to its forms, describing it as “traditional music that sounded

new.”

A Complete Unknown, while telling Dylan’s story

chronologically, bizarrely leaves out certain aspects of Dylan’s personality

and musical background, shedding very little light on Dylan’s artistic

development, and even less on his social and political development. What light

it does shed on his inner life seems distorted, concentrating on the singer’s “psychological

vicissitudes”. During this period, Dylan’s most crucial relationship, both

musically and politically, was with Joan Baez. Dylan was clearly in love with

Baez at the time, with Baez frequently calling Dylan on stage, a move that came

at a time when she was still more famous than he. Their relationship at this

point, in 1964, appears to be a happy and productive one. “We were kids

together” for a short time.

The four years covered by the film were marked by

significant political turmoil. Mangold's treatment of them is pedestrian at

best. As the Marxist writer David Walsh writes, 'In 1961, the British

Trotskyists pointed to signs of a break in the American ice block in several

key layers of society.' '” Among the youth, there has been growing criticism of

the American way of life and an audience for various trends which reflect its

cultural barrenness.” (The World Prospect of Socialism) In the end, this

discontent pointed toward the unresolved contradictions of American capitalism,

the dominant world power and “leader of the free world,” and foreshadowed

significant social upheavals.”

The songs Dylan wrote at the time, such as Masters of War,

Only a Pawn in Their Game, and Hard Rain reflected his awareness of the falsity

of the picture of American life presented in the bourgeois media at the time. For

a short time, Dylan became acutely aware of the reality of postwar America,

including widespread racism and segregated neighbourhoods, the Ku Klux Klan,

the John Birch Society, social inequality, the proliferation of nuclear weapons

and the pervasive anxiety bound up with the Cold War. These events were the

source of the discontent and restlessness that gave rise to his protest songs. James

Brewer writes that Dylan, for a period,

personified that unease and dissatisfaction artistically and intriguingly.

During the years covered by A Complete Unknown,

Dylan was not the only one moving left; significant numbers of young people

began to shift left. However, their radicalism was inevitably confused. As James

Brewer writes, “The musical protest circles were still primarily dominated by

the Stalinist politics of the Communist Party or its intellectual vestiges,

along with a witches’ brew of Maoism, Castroism and the New Left. What had once

been the Trotskyist movement in the US, the Socialist Workers Party, led by

James P. Cannon, essentially broke with Marxism in 1963 and set out on a

wretched, anti-revolutionary course. The

circumstances, in other words, for the artist seeking a genuinely

anti-establishment, anti-capitalist path, free from Stalinist and other malign

influences, were challenging ”[3]

Suffice it to say the British Communist Party were less than

enamoured with Dylan. It saw Dylan as threatening their control of “ British

Music”. In 1951, the Communist Party of

Great Britain (CPGB) published a pamphlet titled "The American Threat to

British Culture." The pamphlet outlined the British CP’s hostility to

young American folk music. The CP followed that pamphlet with its infamously

and thoroughly nationalist British Road to Socialism, a reformist and complete

refutation of Marxism, swapping the world revolution with the Stalinist theory

of ‘socialism in one country’. The British CP were hostile to any outside

influence that would cut across its nationalist path, and that included the

American folk scene.

As Frank Riley writes, “ A debate about ‘purity’ and

‘workers’ songs’ raged in the British folk world, with Ewan MacColl being a

leading protagonist. He eventually reached the absurd position that if a singer

was from England, the song had to be English; if American, the song had to be

American, and so on. There were also detailed definitions of ‘traditional’,

‘commercial’, ‘ethnic’, ‘amateur’, etc. This was adopted as policy in those

folk clubs (a majority) where MacColl and his supporters held sway. Enter Bob

Dylan into this minefield. In 1962, Dylan came to Britain. After some

difficulty getting into the Singer’s Club, based in the Pindar of Wakefield pub

in London, he was allowed to sing three songs, two of them his own.

Contemporary accounts say MacColl and Peggy Seeger, who ran the club, were

hostile. As Dylan was little known, one interpretation could be that Alan Lomax

had talked to them about him. Dylan did not get on well with Carla Rotolo – a

relationship immortalised in Dylan’s Ballad in Plain D: "For her parasite

sister I had no respect" – so this may explain it. Or it may be that they

did not regard his self-written songs as ‘valid’ folk. Later, when Dylan was

pronounced anathema by the CP, MacColl went one step further and announced that

all of Dylan’s previous work in the folk idiom had not been actual folk music.”

A Complete Unknown hints at Dylan’s career ambitions and his

increasing “bitterness and paranoia”. After his most productive period from

1965 to 1968, Dylan seemed to suffer from a catastrophic social indifference. He

was no longer the spokesman of a generation. Mangold’s narrative ends with

Dylan returning to revisit Guthrie, as Brewer states that Mangold was trying to

tie Dylan’s loose ends in a neat bow. However, as Brewer correctly notes, “Unfortunately,

the world is never so tidy.”

It is staggering to see how far the modern-day Dylan is

removed from that political and cultural ferment of the early sixties. As Dylan

admitted, “I don’t know how I got to write those songs. Those early songs were

almost magically written,“ he told CBS. In his memoir, Dylan said, “You must

get power and dominion over the spirits. I had it once, and once was enough.”

The musician Randy Newman concurs, saying, “Dylan knows he doesn’t write like

he did on those first two records.“ That’s not just a quip regarding the

quality; he quite literally doesn’t write the way he used to.

As David Walsh perceptively writes, “Bob Dylan was neither

the first nor the last American popular artist, or artist of any kind, to

imagine he could outwit historical and social processes, which threatened to

'slow down' or even block his rise, by avoiding their most vexing questions and

problems. What he didn’t realise was that in turning his back on social life

and softening his attitude toward the existing order, he was at the same time

cutting himself off from the source of artistic inspiration, that he was

surrendering forever what was best in him.”