La biblioteca de Tito

Entrar en la biblioteca de un escritor asemeja a hurgar de escondidas en el bolsón de instrumentos de un carpintero, de un herrero, de un escultor. Destornilladores, martillos, serrucho, garlopa, formón, taladro, lija, escuadra y cinta métrica para trabajar madera (roble, pino, nogal) con clavos, tornillos, pegamento, barniz y laca, ese universo concentrado en donde residen todas las posibilidades de manufactura y artefacto. Solo que en el extendido mundo de las libreras, apoyadas en la pared como si se fueran a caer, o como si fueran a derribar ese muro, se alinean esas otras herramientas del oficio, clavos y tornillos de papel encerrados entre los lomos de cartón o piel. Sería una banalidad insoportable enunciar: “Dime qué lees y te diré quién eres”, porque se lee de todo, independientemente de los intereses y aficiones, de las obsesiones y manías, de las obligaciones y deberes. A pesar de todo, recorrer los libros que un escritor ha coleccionado en su vida puede proporcionar pistas o coincidencias, quizá esclarecimientos para gozar mejor la lectura de sus libros. A menos que sea un escritor viajero, de esos que el doctor Arévalo retrató en su tiempo: “Cada país, una biblioteca”.

Todo esto viene a cuento por la lectura de Fragmentos del mapa del tesoro, hermoso título para un libro muy especial. Lo escribió Leticia Sánchez Ruiz, escritora ovetense, luego de recorrer la biblioteca que Augusto Monterroso donó a la Universidad de Oviedo. Nos hallamos delante de un itinerario lleno de devoción y reverencia, o, como mejor recita el epígrafe: “con amor, admiración y profundo agradecimiento”. Una curiosidad: la autora nunca conoció en persona a ese autor tan admirado. Estuvo a punto de conocerlo, confiesa, en la presentación de un volumen en Salamanca. Solo que llegó tarde, cuando el acto había terminado: fue la ocasión en que estuvo más cerca de Monterroso. De alguna manera, el libro es una manera de establecer una relación sobreentendida, tácita, virtual.

Es probable que todo haya comenzado con la asignación del Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras a Augusto Monterroso, en el año 2000. Ese premio fue el más importante recibido por el autor guatemalteco. Su estancia en Oviedo habrá sido muy agradable y Monterroso habrá quedado muy bien impresionado. Cuando murió, en 2003, dejó un legado de volúmenes y manuscritos de gran valor. Su esposa, la escritora Bárbara Jacobs decidió, en 2008, donar la mayor parte de esos libros a la Universidad de Oviedo. Esas obras viajaron del barrio de Chimalistac, en la Ciudad de México, a Madrid, por vía aérea. De Madrid, varios camiones cargaron las cinco toneladas del legado y fueron depositados en la Biblioteca del Campus de El Milán. Allí, en una vasta ala del recinto, diversos estantes atesoran años y años de compras, de lecturas, de búsquedas, de entretenimiento, de reflexión, de todo aquello que implica la biblioteca de un autor.

Leticia Sánchez Ruiz nos conduce por una lectura singular, la lectura de varias lecturas, sobre todo, las que Monterroso realizó, y solo el título de una obra serviría para hacer inferencias. Hay, además, libros anotados que nos indican las preferencias de Monterroso y hay manuscritos, cartas, fotografías. No por nada, Sánchez Ruiz denomina a su aventura “fragmentos del mapa del tesoro”, una cita que implica una evaluación. Al principio, relata que, alguna vez, ese tesoro corrió el riesgo de disolverse en la nada, según relata Tito en el cuento Cómo logré deshacerme de quinientos libros. Esa narración contiene una especie de broma, pues el autor dice que, un buen día, decidió desbaratar su colección de libros. Sin embargo, poco tiempo después de empezar, se arrepintió. La anécdota es inventada, pero sirve para ejercitar el sarcasmo del autor guatemalteco. Que se sepa, nunca se deshizo de ningún libro, sino más bien acumuló ejemplares a lo largo de su vida.

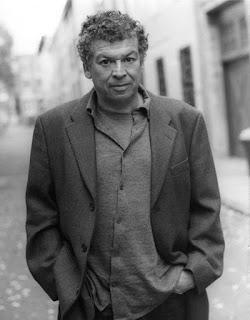

Fragmentos recorre, de puntillas, los estantes ordenados, que, no obstante ese concierto, forman un laberinto de símbolos y signos, listos para ser interpretados. El camino entre los rimeros de volúmenes sirve a la autora para tejer un retrato de Tito Monterroso, que mezcla biografía, anécdotas literarias y citas textuales, y trata de que esa pintura sea lo más fiel posible al original. Una de las partes más interesantes se encuentra en las anotaciones que Tito escribió en las páginas de sus lecturas favoritas.

Inicia con una cita de Steiner: hay dos tipos de personas, las que leen con un lápiz en la mano y las que no. “No hay nada tan fascinante como las notas marginales de los grandes escritores”, dice. Obviamente, Tito Monterroso leía con un lápiz en la mano. Su trazo es tímido, poco enfático. Sánchez señala que la característica de las anotaciones de Tito consiste en que más que comentar, corrige. Quién sabe si ese es el resultado de su primer trabajo en México, corrector de pruebas en la editorial Séneca. De todas formas, crea un código personal: una equis para los errores de traducción; un signo de interrogación, como una ceja levantada, ante lo erróneo o lo incomprensible; un corchete para lo que le agrada; una estrella de seis puntas para lo excepcional, y para las frases que mencionan a las moscas, una de las extrañas obsesiones del autor guatemalteco.

Monterroso señala, en Cuaderno de notas, de Henry James, los párrafos en los que el norteamericano se queja de la excesiva vida social, que no le deja tiempo para la escritura, en cuanto refleja, dice Sánchez, algo que el mismo Tito reflexionaba en el texto Agenda de un escritor. En otro libro, El loro de Flaubert, de Julian Barnes, Monterroso subraya la afirmación: “Flaubert no tenía una idea muy exacta de cómo eran los ojos de Emma Bovary”. Esto lo lleva a buscar, en el texto, la comprobación de tal observación, y subraya las partes en las que aparecen los ojos de la protagonista: “sus ojos negros parecían más negros”; “negros en la sombra y de un azul oscuro a plena luz”; “aunque eran pardos parecían negros”. Parecería extraña esta ambigüedad en un autor que se pasaba una semana a la búsqueda de la mot juste, mas la duda se disuelve cuando se piensa que la indeterminación es una de las claves de la literatura. Monterroso también subraya los libros de Borges y de Cortázar y uno podría pensar que los subrayados, entonces, son signos de admiración, en el mejor sentido del término.

Leticia Sánchez Ruiz señala, como una curiosidad casi metaliteraria, que en la biblioteca de Tito se encuentran las obras de Arturo Monterroso y de Porfirio Barba Jacob. Declara, con un cierto asombro, que Arturo Monterroso existe realmente y que se trata de un escritor guatemalteco. Puedo confirmar esa intuición: Arturo no solo existe en la realidad, sino que es un excelente escritor, muy admirado por los innumerables alumnos de sus cautivadores talleres literarios. Sus obras no se parecen en nada a las de Tito, y eso está muy bien, porque aleja sospechas y aprovechamientos de literarias casualidades. De Barba Jacob indica la casi coincidencia con el nombre de Bárbara Jacobs, la esposa de Monterroso. Completa la información diciendo que Tito conoció a Barba Jacob, porque este frecuentaba la casa de sus padres, y que Tito lo admiraba mucho. Hay mucho más. Porfirio Barba Jacob fue un modernista colombiano que se estableció en Guatemala, hizo escuela allí, fue amigo y enemigo de Rafael Arévalo Martínez, y mereció una biografía escrita por Fernando Vallejo. Tenía razón Tito cuando guardaba sus libros. Fragmentos de un mapa del tesoro contiene mucha más información, y su lectura nos revela el mundo monterrosiano y nos incita a lo que sería la actividad principal: leer la obra de Tito, o, lo que es casi lo mismo, releerla, porque es prosa para degustar una y otra vez.

The Library of Augusto Monterroso

Posted bydantelianocuenta9 July, 2025

Posted inArticles Tags:Dante Liano, Monterroso

Entering a writer's library is like rummaging through the toolbox of a carpenter, a blacksmith, or a sculptor. Screwdrivers, hammers, saws, garlopa, chisel, drill, sandpaper, square and tape measure to work wood (oak, pine, walnut) with nails, screws, glue, varnish and lacquer, that concentrated universe where all the possibilities of manufacture and artefact reside. Only that in the extended world of bookcases, leaning against the wall as if they were going to fall, or as if they were going to tear down that wall, those other tools of the trade are lined up, nails and paper screws enclosed between the cardboard or leather spines. It would be an unbearable banality to say: "Tell me what you read and I'll tell you who you are", because you read everything, regardless of interests and hobbies, obsessions and manias, obligations and duties. Despite everything, going through the books a writer has collected throughout their life can provide clues or coincidences, perhaps clarifications that help better enjoy their books.

Unless he is a travelling writer, one of those that Dr. Arévalo portrayed in his time: "Each country, a library." All this comes to mind by reading Fragments of the Treasure Map, a beautiful title for a very special book. It was written by Leticia Sánchez Ruiz, a writer from Oviedo, after touring the library that Augusto Monterroso donated to the University of Oviedo. We are before a journey full of devotion and reverence, or, as the epigraph best recites: "with love, admiration and deep gratitude". A curiosity: the author never met this admired author in person. He was about to meet him, he confesses, at the presentation of a volume in Salamanca. Only that he arrived late, when the event was over: it was the occasion when he was closest to Monterroso. In a way, the book is a way of establishing an implied, tacit, virtual relationship.

It all likely began with the awarding of the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature to Augusto Monterroso in the year 2000. That award was the most important one received by the Guatemalan author. His stay in Oviedo will have been very pleasant, and Monterroso will have been very well impressed. When he died in 2003, he left a legacy of volumes and manuscripts of great value. His wife, the writer Bárbara Jacobs, decided, in 2008, to donate most of these books to the University of Oviedo. These works travelled from the Chimalistac neighbourhood in Mexico City to Madrid by air. From Madrid, several trucks loaded the five tons of the legacy, and they were deposited in the Library of the El Milán Campus. There, in a vast wing of the enclosure, various shelves treasure years and years of shopping, reading, searching, entertainment, reflection, everything that an author's library implies.

Leticia Sánchez Ruiz leads us through a singular reading, the reading of several readings, especially those that Monterroso made, and only the title of a work would serve to make inferences. There are also annotated books that indicate Monterroso's preferences, and there are manuscripts, letters, and photographs. Not for nothing, Sánchez Ruiz calls his adventure "fragments of the treasure map", a quote that implies an evaluation. At the beginning, he relates that, once, that treasure ran the risk of dissolving into nothingness, as Tito relates in the story How I managed to get rid of five hundred books. That narrative contains a kind of joke, because the author says that one day, he decided to dismantle his collection of books. However, shortly after starting, he regretted it. The anecdote is invented, but it serves to exercise the sarcasm of the Guatemalan author. As far as is known, he never got rid of any book, but rather accumulated copies throughout his life.

Fragments tiptoe through the orderly shelves, which, despite this concert, form a labyrinth of symbols and signs, ready to be interpreted. The path between the volumes serves the author to weave a portrait of Tito Monterroso, which mixes biography, literary anecdotes and textual quotations, and tries to make that painting as faithful as possible to the original. One of the most interesting parts is found in the notes that Titus wrote on the pages of his favourite readings. It begins with a quote from Steiner: There are two types of people, those who read with a pencil in their hand and those who do not. "There's nothing quite as fascinating as the marginal notes of great writers," he says. Tito Monterroso was reading with a pencil in his hand. His stroke is shy, not very emphatic. Sánchez points out that the characteristic of Tito's annotations is that, rather than commenting, he corrects. Who knows if that is the result of his first job in Mexico, proofreader at the Séneca publishing house. In any case, create a personal code: an X for translation errors; a question mark, like a raised eyebrow, in the face of the wrong or the incomprehensible; a bracket for what pleases him; a six-pointed star for the exceptional, and for phrases that mention flies, one of the Guatemalan author's strange obsessions.

Monterroso points out, in Henry James's Notebook, the paragraphs in which the American complains about the excessive social life, which leaves him no time for writing, as it reflects, says Sánchez, something that Tito himself reflected on in the text Agenda de un escritor. In another book, Flaubert's Parrot, by Julian Barnes, Monterroso underlines the statement: "Flaubert did not have a very exact idea of what Emma Bovary's eyes were like." This leads him to seek, in the text, the verification of such an observation, and underlines the parts in which the protagonist's eyes appear: "her black eyes seemed blacker"; "black in the shadow and from a dark blue to full light"; "although they were brown, they looked black." This ambiguity would seem strange in an author who spent a week in search of the mot juste, but the doubt dissolves when one thinks that indeterminacy is one of the keys to literature. Monterroso also underlines the books of Borges and Cortázar, and one might think that the underlines, then, are exclamation marks, in the best sense of the term.

Leticia Sánchez Ruiz points out, as an almost metaliterary curiosity, that in Tito's library are the works of Arturo Monterroso and Porfirio Barba Jacob. He declares, with a certain astonishment, that Arturo Monterroso exists and that he is a Guatemalan writer. I can confirm that intuition: Arturo not only exists in reality, but he is an excellent writer, greatly admired by the countless students of his captivating literary workshops. His works are nothing like Tito's, and that is very good, because it removes suspicions and exploitation of literary coincidences. De Barba Jacob indicates the almost coincidence with the name of Bárbara Jacobs, Monterroso's wife. He completes the information by saying that Titus knew Barba Jacob, because he frequented his parents' house, and that Titus admired him very much. There is much more. Porfirio Barba Jacob was a Colombian modernist who settled in Guatemala, was schooled there, was a friend and enemy of Rafael Arévalo Martínez, and deserved a biography written by Fernando Vallejo. Titus was right when he kept his books. Fragments of a Treasure Map contains much more information, and reading it reveals to us the world of Monterrosian and incites us to what would be the main activity: reading Tito's work, or, what is almost the same, rereading it, because it is prose to be enjoyed over and over again.

The Other Side: Stories of Central American Teen Refugees Who Dream of Crossing the Border Written by Juan Pablo Villalobos translation by Rosalind Harvey, Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2019

This is an important compilation of stories from unaccompanied Central American teenage refugees who risk death to cross the U.S.–Mexico border. Recounted in short vignettes readers learn about the harrowing journey and treatment meted out to young children seeking a better life for themselves and their family. Juan Pablo Villalobos’s introduction indicates that all these stories are true except when he wrote their story to protect some minors’ identities.

The book is aimed at a 12+ audience. It contains significant allusions to violence, including murder and sexual assault. Which unfortunately adds to the compelling nature of the stories. The book is presented in such a way that it works on many levels.

Most of the children are from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. Such is the massive scale of the problem that in 2016 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees published a major report called Children on the Run: In one interview with 15-year-old Maritza, from El Salvador, she explained to researchers that “I'm here because I was threatened by the gang. One of them "liked" me. Another gang member told my uncle that he should get me out of there because the guy who liked me was going to do me harm. In El Salvador, they take young girls, rape them and throw them in plastic bags. My uncle told me it wasn't safe for me to stay there, and that I should go to the U.S.”[1]

Juan Pablo Villalobos called this collection nonfiction because the stories were collected via first-person interviews. The book is based on a series of interviews Villalobos held did in 2016; The Other Side examines Central American migration through the stories of 10 children who made the murderous trip to the U.S. on their own.

Villalobos adds , my literary ambition, if I can admit to that, was to write a book that is about Central American immigration and the migration of unaccompanied minors, but these stories are happening all over the world — in Syria, in the north of Africa, in Europe — and it was my hope that the book should resonate beyond the specific moment and the American and Central American contexts.”

With the Fascist Trump in the White House, the situation will only get worse. Figures released recently by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) revealed that the United States has detained record numbers of unaccompanied minors attempting to cross its southwestern border. In the last few days, various US media have reported, that the Trump White House is imminently planning to invoke the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as part of his administration’s ongoing criminal deportation operations.

Leaving Guatemala for AmERiCa by David Unger

In 1957, when I was not quite seven, I discovered that social relations in the United States were governed by race and ethnicity. It was a Saturday morning, and my parents, two brothers and I were eating breakfast around the green Formica table in our Hialeah, Florida kitchen. The windows were cranked wide open and still it was fry-eggs on-the-sidewalk hot, years before air-conditioning became an affordable option. Imagine living through a Florida summer that begins in May and ends in October, 12 miles from the beach, fans circulating swampy mosquito-laden air. Immobile air.

A voice shot through the windows.

“Tomato boy. Tomato boy.”

I ran to our jalousie-window front door and opened it. A twelve-year-old boy, wearing a tight short sleeve shirt and black pants eyed me with an expression of resignation and boredom.

He stood three steps below me holding a reed basket filled with fist-sized red bursts. “ — matoes? dollah a box, “ he drawled. His skin was purple and smooth as a plum. He was shoeless. How could his bare feet bear the weed stickers, the burning asphalt?

Another lanky teenage colored boy, as African Americans were known back then — if you used the polite term — sat at the back of a green late 40’s Ford pickup truck; stacks of boxed tomatoes rose along the wooden side rails beside him. This sixteen-year-old wore a white tee shirt and seemed happy to be sitting. An older Negro (another fifties appellation) leaned his arm against the driver side window. The engine coughed, grey smoke puffed and putted out of the muffler.

I ran back to my parents and told them that the tomato boys were here and that the tomatoes looked yummy. My mother took a dollar out of her change purse.

I gave the boy the bill.

He put a four-pound box in my arms. “I need it back,” he said, tapping the box. His forehead was beaded in sweat.

I nodded, smiling, and he grinned back. If he hadn’t been working, we could have played catch, Indian Ball or Flies and Grounders in our back yard. I knew a lot about baseball already — reading the Sports page of The Miami Herald had made me an English reader. This kid could be another Mays or Robinson, maybe even a Satchel Paige.

My parents Luis y Fortuna, with my brothers Leslie y Felipe and me in the white sweatshirt.

Could I ever really be friends with this boy?

Most likely he lived on a farm and didn’t go to school. Because he was “colored,” he wouldn’t be allowed into the Food Fair, Rexall’s Drug Store or Schell’s Hobby Shop. Maybe his Pop could buy a six pack at Mike’s Liquor if he trusted a white guy with his money.

The tomatoes were perfectly round. They were grown in fields about a mile away, in Opa-locka, behind the airbase. In colored town. I’d been warned by Jerry Easley never to ride my bike in “Niggertown.” “One them “jungle bunnies” will steal your bike, Jewboy.”

From a 1956 Miami Herald article about this “immigrant family” fleeing “Communism” in Guatemala

When we came to the U.S. from Guatemala in 1955, my father was already 57. There was a recession in Florida, one of the state’s never-ending rags-to-riches and riches-to rags seesaw. There were no job opportunities for anyone, certainly not the elderly, especially if they had weird accents. My father’s English was heavily German-inflected.

After emigrating to Guatemala in 1933, he ran the Royal Home, a combination hotel and restaurant for British nationals. Then later, he managed the canteen at the American base, though he’d fought for Germany, during the first world war. Before coming to America, he and my mother had opened La Casita, a restaurant that served champagne, steaks and Lobster Newburgh, which became Guatemala City’s best restaurant. In our last year there, my parents won the concession to supply Pan American Airways with hot meals for passengers on their newly established routes to Central America.

My father was a people person. In the 1920’s, after the war, he’d managed a troupe of magicians who traveled from Hamburg all the way to Cartagena and Guayaquil. He was cultured and gregarious — he dressed in wool suits and was always polite and deferential. He sold tickets at a movie house in Guatemala City and then took a slow boat to China where he was the night clerk in Shanghai’s famous Palace Hotel, before the Japanese invaded and he returned to Guatemala.

My father witnessed the Japanese invasion of China in 1937. He was the night clerk at the Palace Hotel. He told us that the Japanese soldiers went in the hotel and pulled out any Chinese and shot them pointblank.

He had an impossible time getting a job in Miami, but finally he was hired as a host at a Dobb’s House, a restaurant on West 36th Street, across from the then fledgling Miami Airport and a long bus ride from our Hialeah home. It was his kind of job — greeting and seating guests. The only problem was his high standards: he was critical when his manager substituted paper for cloth napkins his first week of work and when he overheard the manager cursing the Negro dishwashers as “lazy beasts.”

One day, a couple came into the restaurant. My father escorted them to a table near the air-conditioner. During the meal, the manager came up to my father and asked why he had seated “them niggers” in an area reserved for white people. My father said that he didn’t know there were different sections for people of different colors in the restaurant.

“Can’t you see they’re black?”

“And so? What difference does that make?” He had previously worked six months for the railroad in Livingston, Guatemala, a totally Garifuna village.

“Unger, next time a couple of “niggers” come, sit them in the back.”

“But it’s too hot back there.”

“You do what I tell you to do!”

That was my father’s last day working at Dobb’s House.

There were no colored kids in my Palm Springs Elementary School in Hialeah though I knew that some lived closer to the school than me. Also, few Latinos.

My classmates were the children of working-class parents: airline mechanics, policemen, plumbers, milkmen and the occasional single mother cocktail waitress or on rare occasions, a cashier at the Food Fair or a hairdresser at the local salon. None of our neighbors had college degrees, none spoke a word of Spanish. They knew nothing of opera or art, like my father. None were Jewish.

When a classmate got angry at you, he’d call you tomato boy or nigger. It was normal. My brothers and I never called anyone “nigger” because it was an ugly sounding word and we had often been called kikes, spics and dirty Jews; we had black eyes and curly hair to prove we were foreigners. One Saturday morning we found that someone had thrown rotten eggs against the side of our house. Another time someone painted a wooden wire roll with the words “Dirty Jues. Get out.” Like the tomato pickers, we suspected that we weren’t really welcomed.

One afternoon when I was sixteen or so my father and I were at Miami International Airport, waiting for my mother to return from visiting her mother in Guatemala. We were walking down the concourse when we suddenly saw a towering Negro, well over six feet tall, walking towards us. He was busting out of a suit that barely concealed rippling muscles. The man was quite handsome, with short-cropped hair and a smile that implied royalty.

We knew it was Muhammad Ali. He was in Miami training at the 5th Street Miami Beach gym to fight Big Cat Cleveland Williams later in the year. A two-time felon, Williams, was a puncher with a mustache and a bullet still lodged in his hip to underscore his mettle. But all his power proved hopeless when Ali scored a decisive 3rd round TKO at the Astrodome in November of 1966.

My father was all of five foot eight and a fiery boxing fan. We religiously watched the Wednesday and Friday Cavalcade of Sports fights on television with him. We loved Luis Rodriguez, Floyd Patterson and Federico Fernandez who had style and hated boxers like Carmen Basilio and Gene Fullmer who pummeled their opponents during clinches, threw low blows when the referee’s vision was blocked, delivered rabbit punches that hammered the back of their opponent’s necks. Emile Griffith was our favorite boxer though he “killed” Benny ‘Kid’ Peret in the ring after continuously taunting the gay boxer by calling Griffith a “maricon.”

Ali was ballet encapsulated — handsome, witty, and defiant. He wasn’t colored or a Negro — he was beyond classification. He was a proud black man with the gift of gab. My father admired him not only for his boxing, but because he spoke his mind and somehow, unlike himself, seemed to revel in his audacity.

We went up to Ali. “I want to shake your hand,” my father said to him.

Ali smiled and shook my father’s puny mitt.

“You make your people proud,” my father said, barely able to spit out his words in an intelligible English.

“Thank you,” said the champ, a bit bemused.

Ali gave me his autograph on a card that had the fight song of my new high school in Miami Springs on it. As he was signing, my father added: “You know, you can come to my house for dinner any time you want.”

What my father was saying was that in separate-raced Miami where signs warned blacks and dogs to stay out of Miami Beach after 6 PM, my father would be honored to break bread with Muhammad Ali despite what the neighbors would say…

“I just might do that,” Ali said. He smiled in a way that made me think he understood what my father meant.

In 1964, when I was in the middle of 9th grade, my parents had moved from Hialeah to Miami Springs — from a house with no air-conditioning to one with central air. As soon as we moved in, that first week, we had worshippers from the local Methodist, Lutheran and Baptist churches come and visit. We never told them we were Jewish, only that we were not interested in religion.

In 10th grade, I took a World Humanities seminar taught by Mr. Gonzalez, a Cuban exile. It was a course in which we read Gordon Allport’s The Nature of Prejudice and Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer and discussed race, Communism, The John Birch Society and the Vietnam War. We read The World’s Great Religions, and defined what made someone an atheist or an agnostic. We listened to classical music and compared Mozart to Beethoven to Stravinsky.

There was one black kid in the class. Skid was a towering, skinny kid who sported a scraggily goatee. He always wore black shades even indoors and he would look over their tops when he whispered to me sitting beside him. He had a nice smile and a very red tongue which protruding from his buckteeth.

His mother had been coming to our house once a week to do the ironing and the folding since my mother worked full-time as a secretary at Pan American Airways. Skid and his mother lived across the canal from Miami Springs in the black part of Hialeah. The poor treeless part where the streets were rutted and the telephone poles wobbled.

Skid and I breached the racial divide five days a week. We really liked each other. He talked like a Black Panther and I like a future Students for a Democratic Society member.

We agreed that Satch Paige of the Negro Leagues was probably the greatest pitcher ever, till Sandy Koufax, a Brooklyn southpaw, calmed his wildness and went 25–4 and won pitching’s Triple Crown in 1963. He was Jewish and his refusal to pitch on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, made him a hero in the larger Jewish community. But we both understood why it was necessary to have different heroes that reflected our ancestry without talking about it.

In our senior year in 1968, Mr. Gonzalez, invited us to be on a local TV show that aired on Saturday mornings called “Youth and the Issues.” I remember sitting in the lobby with Skid, his mother and my mother waiting for our moment to go film our segment. Martin Luther King had been assassinated a month earlier and Newark and Gary, Indiana had gone up in flames. LBJ had decided not to seek re-election and the Vietnam protest movement was in full throttle.

I remember that our host, a likeable liberal, was more interested in getting across his argument that democratic America would find peaceful solutions to each and every one of our problems. He was a happy warrior ala Hubert Humphrey style. Skid spoke admiringly of Huey Newton and Stokely Carmichael, claimed Malcolm X was the man; I admired Ernest Gruening, William Fulbright and Al Gore’s father, all of whom had voted against the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. I remember we had fun on that show, frightening our host. But what the hell? In the lobby, Skid went home with his mother and I with mine. It was a beyond awkward when Skid’s mom said to us: “See you on Saturday morning.”

In my yearbook Skid wrote something like “Say brother. With your bright mind and good heart you are going to go far in life. One day maybe our children will play together. Keep being the way you are.”

Skid’s words nearly broke my heart. He knew that the gap between us, in southern Florida, had been insurmountable for teenagers of our generation. There would have been hope for his dream to be true, but I had already decided that I wanted to get as far away from Miami as I could. I eventually ended up in Boston and later learned that Skid had enlisted to fight in Vietnam.

The separation of races was entrenched in Miami. The Negroes lived in Opa- Locka, Allapattah, Overtown and a hot and ghetto city called paradoxically Liberty City — this is where my brother and I went to buy beer in high school, giving young black men a fifty cents tip to get us a six-pack of Busch Bavarian for $2.50.

Miami Negroes were very angry when during the Kennedy Administration thousands of Cubans came to Miami to escape Castro and were given several hundred dollars as soon as they arrived. Then Cuban adults received $100 a month for a whole year to get readjusted in the U.S. At the time, the minimum wage was a buck and a quarter in Miami, which meant that if you worked a 40-hour week you earned $150 a month after taxes. Nobody ever gave the colored people any support when they came to Miami from Georgia, Louisiana and Alabama to work as crop pickers. Or should I say from Palatka or Pensacola, Florida, where many of their relatives had at one time been lynched.

Within two years, the industrious Cuban exiles had bought up most of the gas stations and shoe repair shops in Miami and soon replaced the black porters and maids in most of the Miami Beach hotels. Calle ocho, less than a mile from Liberty City, became the main thoroughfare for them.

The Negroes had no choice but to sit on their hands and watch. Eventually they rioted later in 1968 Frankly, who could blame them? Unfortunately, they burned down, in frustration, the few businesses in their neighborhoods which would then take decades to rebuild.

By the time Obama became president in 2008, I had lived in New York City for upwards of 35 years. My wife and I campaigned for him on the outskirts of Philadelphia, in a poor white ghetto that reminded me of the Hialeah of my youth. White people answered their doors suspiciously. They didn’t know who John McCain was; I think many thought Obama was trying to oust George W. Bush — their kind of American — from the White House. It was a rough day of door knocking, in the pouring rain. Our solace was when we knocked on the door of a black family, whose hearts welled up with pride at seeing two white fifty year olds campaigning for their man — think Satchel Paige — in the cold, pouring rain. We gave their kids all our Obama buttons, which we were supposed to sell for a dollar each. His election seemed providential: maybe my adoptive country had finally achieved the greatness of what the Constitution says should be a “more perfect union.”

I wonder if Skid made it out of Vietnam and returned to Hialeah. Did he ever become an electrician? Under different circumstances, I think we might’ve stayed friends, but the social and racial gap between us in the ’60s, in the south, was titanic.

David Unger received Guatemala’s Miguel Angel Asturias National Literature Prize for lifetime achievement in 2014, though he writes in English and lives abroad. Novels include In My Eyes, You Are Beautiful (Mosaic Press, 2023), The Mastermind, (Akashic Books, 2016) [translated into ten languages including Spanish, Arabic, Italian, Turkish and Polish], The Price of Escape (Akashic Books: 2011; into German, Romanian and Spanish) and Life in the Damn Tropics (Wisconsin University Press, 2004). He has translated 18 titles including his celebrated re-translation of Guatemalan Nobelist Miguel Angel Asturias’s Mr. President (Penguin Classics, 2022), Folktales for Fearless Girls (Penguin, 2019), The Popol Vuh, (Guatemala’s pre-Columbian creation myth) and books by Rigoberta Menchú (Guatemala), Enrique Lihn (Chile), Silvia Molina (Mexico), Nicanor Parra (Chile), Ana Maria Machado (Brazil), Elena Garro (Mexico) and Teresa Cárdenas (Cuba). He has also translated many stories by Mario Benedetti (Uruguay), Denise Phe-Funchal (Guatemala), Sergio Ramirez Mercado (Nicaragua), among others.

His children’s books are José Feeds the World (Duopress, 2024), Moley Mole/Topo Pecoso (Green Seeds Publishing, 2021). Sleeping With the Light On (Groundwood Books, 2020), and La Casita (2011, CIDCLI).

Other books include Ni chicha, ni limonada (F y G Editores, 2019, 2009) ). His short stories and essays have appeared in the Paris Review, Medium, Puertos Abiertos (FCE, 2011), Guernica Magazine (February 2016, April 2011, November 2007 and August 2006) and Playboy Mexico (October 2005).

Mr President by Miguel Ángel Asturias Translated by David Unger-Foreword by Mario Vargas Llosa- introduction Gerald Martin-Penguin Classics Paperback July 2022-320 pages

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” Miguel Ángel Asturias 1973.

The Latin American novel, our novel, cannot betray the great spirit that has shaped – and continues to shape – all our great literature. If you write novels merely to entertain – then burn them!

Miguel Angel Asturias

“The great works of our countries have been written in response to a vital need, a need of the people, and therefore almost all our literature is committed. Only as an exception do some of our writers isolate themselves and become uninterested in what is happening around them; such writers are concerned with psychological or egocentric subjects and the problems of a personality out of contact with surrounding reality.”

Miguel Ángel Asturias

“Life is not an easy matter…. You cannot live through it without falling into frustration and cynicism unless you have before you a great idea which raises you above personal misery, above weakness, above all kinds of perfidy and baseness.”

― Leon Trotsky, Diary in Exile, 1935

Generally speaking, art is an expression of man’s need for a harmonious and complete life, that is to say, his need for those major benefits of which a society of classes has deprived him. That is why a protest reality, either conscious or unconscious, active or passive, optimistic or pessimistic, always forms part of a really creative piece of work. Every new tendency in art has begun with rebellion.

Art and Politics in Our Epoch (1938)

Translation is often an act of revelation—of revealing what is hidden -David Unger

Nobel Prize-winning Guatemalan author Miguel Ángel Asturias’s masterpiece Mr President was published in 2022 by Penguin. It is the first English translation in more than half a century. Translated by award-winning writer and translator David Unger and features a foreword by Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa and an introduction by the writer and biographer Gerald Martin.

Asturias’s Mr President was inspired by the 1898–1920 presidency of Manuel Estrada Cabrera. The novel was subsequently banned in Guatemala. Miguel Ángel Asturias’s novel is a surrealist masterpiece, and a devastating attack on capitalism not just in Guatemala but around the world. It is to Penguin’s credit that such an important book has been given the translation it deserves. The new Penguin Classics edition is timely. David Unger says, “Mr. President has more to say to an American in 2022 than it did in 1962 when we knew less about the shenanigans of the CIA and the liaison between the military and the industrial complex.”

Miguel Ángel Asturias (1899-1974) was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1967, the first Latin American novelist to receive such an honour. Although one of his main occupations was as a diplomat he is primarily known as a fiction writer.

Mr President, although written from 1922 to 1932, wasn’t published until 1946 partly due to self-censorship and was also banned by the Guatemalan state. Asturias quite rightly feared that President Ubico (1931-1944) would assume that he was the dictator being depicted.

Foreword

The foreword is by Mario Vargas Llosa. Llosa is the noble Prize author of twelve novels, including Death in the Andes, In Praise of the Stepmother, The Storyteller, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, and The War of the End of the World, 1995, he was awarded the Cervantes Prize, the Spanish-speaking world's most coveted literary honour, and the Jerusalem Prize. His recent book Harsh Times was a described by Hari Kunzru, as "A compelling and propulsive literary thriller “in his New York Times Book Review.

Llosa correctly states “Mr. President is qualitatively better than all previous Spanish language novels and one of the most original Latin American texts ever written. He continues that without Asturias, “there would be no García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Isabel Allende, Laura Restrepo, Laura Esquivel, José Lezama Lima, or Roberto Bolaño.”

Llosa believes that Miguel Ángel Asturias “wasn’t fully aware of how great a novel he had written and whose magnitude he would never again repeat, because the novels, short stories, and poems he wrote afterward were closer to the narrower, somewhat demagogic literature of “committed” dictator novels that he had earlier championed. He hadn’t realized that the great merit of Mr. President was precisely that he had broken that tradition and raised the politically engaged novel to an altogether higher level “.[1]

Introduction

Every great author needs someone who will defend their work to the death if necessary. Miguel Asturias has Gerald Martin. Martin who is the author of the superb biography of García Marquez is currently working on a biography Vargas Llosa. Penguin will publish Asturias’s Men of Corn in 2025[2]. Martin has translated and written a foreword for the new book. In his introduction to “Mr. President” Martin writes “What is magical realism, if not the solution to writing novels about hybrid societies in which a dominant culture of European origin is juxtaposed in multiple ways with one or more different cultures that in many cases are ‘premodern’? It was not Gabriel García Márquez who invented magical realism; it was Miguel Ángel Asturias.”

What makes Mr President such an important book. Martin elaborates “it’s a novel 'very like a play, a tightly concocted drama (at times a theatre of marionettes),' equally cinematic and poetic. It is reminiscent of Kafka and Beckett in its surreal flights within the consciousnesses of the mad or dying, or within the narrative of myth ... The novel’s vision is relentlessly dark, but its execution is exhilarating, daring, even wild. Asturias’s boldness is repeatedly arresting, and his descriptions unforgettable...Such electrifying vividness animates every page”.

Translation

All great books need a great translation. After fifty years Mr President finally has that kind of translation, David Unger fully deserves the plaudits his translation has received. In 2014, Unger was awarded the Miguel Ángel Asturias National Prize in Literature for lifetime achievement, the most important literary prize in Guatemala. As a debt of gratitude to the country of his birth Unger decided to take on a new and difficult translation. The main purpose was to restore this great novel to the pantheon of world literature.

Having read the previous publication of the novel with the translation by Fraces Partridge I was curious to find out Unger’s opinion. Unger told me in an interview I did with him on my website “Partridge’s translation is mostly workman-like but suffers, as I say in the introduction, with many Anglicisms and a failure to recognize many Guatemaltequismos—particularly Guatemalan words and terms that she didn’t fully understand. Mr. President is a very American novel, one that lends itself to translation in the American vein. Words like “coppers,” “blimey,” and “lorry” are acceptable terms in the English language but are not inviting to North American readers. Further, she didn’t have a clue about certain Guatemalan foods, birds and plants that have entered the American vernacular through the immigration of nearly 60 million Latin Americans into the U.S. In some ways, she was hopelessly overmatched though I find that she also came through with some lovely descriptions, a la Bloomsbury style.[3]

It is perhaps an understatement to say that translating this book was an extraordinarily difficult undertaking. But David Unger’s lucid and masterful new translation of Mr President presents an opening for a new generation of readers around the world to appreciate this “influential, and wrongly maligned masterpiece”.

Joel Whitney writes “Mr. President is decidedly hard to translate, as it relies on poetic alliterations and onomatopoeia, devices learned from surrealism’s inventors and other avant-garde movements. But it also relies on Asturias’s very keen ear to the street, his love of myth and Indigenous culture, and Unger proves to be a masterful transformer. Much of the translation is truly of another time, rendering not just Central American Spanish but also Guatemalan neighbourhood-, class-, and period-specific slang. The praise for Unger’s translation is highly deserved. But the fact of Penguin Classics and Unger choosing this unfairly suppressed book is long overdue, the wait like being unburied, with your eyes open”.[4]

As Whitney says in his article the release of Asturias’s Mr President could not be timelier. As Unger explains “I wanted the novel to really speak to our generation and our time,” It is not only in Latin America that the tyranny of the dictator’s rule, but this tyranny is a global phenomenon. The current genocide being carried out in Gaza by the Israeli fascist government is but one example of this worldwide trend of the rule of the dictators. The Israeli president Netanyahu’s speech before Congress, showed that this fascist war criminal still defended genocide in Gaza, stating, “This is not a clash of civilizations. It’s a clash between barbarism and civilization. It’s a clash between those who glorify death and those who sanctify life.”[5] The reception Netanyahu’s speech received by the flunkeys in the White has been compared to that of Adolf Hitler when he addressed the German parliament in the 1930s.

The CIA and the Suppression of Mr President

As I said in the introduction Asturias’s novel although finished in 1932 was not published until 1946. What is perhaps not so well known is the role of the United States Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) role in the suppression of this great novel. This criminal act is one of the reasons why Asturias has not had the international recognition his work deserves. This is not the case in Latin America where the novel according to literary scholar Gerald Martin was “the first page of the Boom.[6] Without Asturias, [the Boom] might not have developed.” Said Martin.

Asturias’s novel was released at the beginning of the Cold War. Latin America was seen by the United States as its own backyard and began installing several right-wing dictatorships many of which carried out genocide on an industrial scale. On the cultural front it helped set up and backed the Congress for Cultural Freedom[7], an anti-Communist front created to push pro-American articles and stories through magazines like Mundo Nuevo and other similar magazines around the world such as Encounter. To his credit Martin defended Asturias and opposed this right-wing organisation and its puppet magazines. Martin played no small role in discrediting this CIA front.

Miguel Ángel Asturias was born on October 19, 1899, one year after dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera came to power. “My parents were quite persecuted, though they were not imprisoned or anything of the sort, “said Asturias. The treatment of his parents no doubt heavily influenced not only his decision to write about injustice and social inequality throughout Latin America but to become an activist. Asturias joined the Generation of 1920, and became politically active organising organize strikes and demonstrations. As Asturias writes in his Nobel Prize speech “All Latin American literature, in song and novel, not only becomes a testimony for each epoch but also, as stated by the Venezuelan writer Arturo Uslar Pietri, an “instrument of struggle”. All the great literature is one of testimony and vindication, but far from being a cold dossier these are moving pages written by one conscious of his power to impress and convince”.[8]

Asturias’s Mr President was groundbreaking in so many ways. As Joel Whitney points out in his excellent article[9] Mr President was published five years before George Orwell’s 1984, and captures the mass propaganda uses of new technologies: Asturias writes: “Every night a movie screen was raised like a gallows in the Plaza Central. A hypnotized crowd watched blurred fragments as if witnessing the burning of heretics. … Society’s crème de la crème strolled in circles … while the common folk gazed in awe at the screen in religious silence.” This fear proves atmospheric, as the president’s favourite advisor, Miguel Angel Face, undertakes a secret mission: to prompt the president’s main rival, a general, to go on the run. Why? The president needs a scapegoat, and running is a confession of guilt, he says. But irony is in constant collision with this fear, mirroring the young Asturias’s wonder at the discredited, delusional imprisoned dictator. Unaware that the president has orchestrated the general’s escape, a judge advocate shouts, “I want to know how he escaped! … That’s why telephones exist; to capture government’s enemies.” This judge also warns a suspected witness: “Lying is a big mistake. The authorities know everything. And they know you spoke to the General.”[10]

As was mentioned earlier Asturias played a central role in the development of the Boom movement. This movement consisted of a relatively young group of writers, Cortázar; Vargas Llosa; Gabriel García Márquez, of Colombia; and Carlos Fuentes, of Mexico, to name but a few of the better-known authors. Asturias was recognised as their natural predecessor. And was credited with the invention of Latin American magical realism which went on to influence the likes of García Márquez. Instead of acknowledging his debt to Asturias Garcia Marquez somewhat ungraciously denied Asturias had any influence on his work.

According to Graciela Mochkofsky “Many of the Boom authors, starting with García Márquez, dismissed Asturias’s work as archaic, and denied that it had any influence on their writing. Asturias didn’t help matters when, during an interview, he agreed with a suggestion that García Márquez, in “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” had been heavily influenced or even plagiarised Balzac’s “The Quest of the Absolute”.[11]

It must be said that Asturias prodigies were a little ungrateful to their master. Julio Ramón Ribeyro defended Marquez saying, “it is difficult to find authentic points of reference between García Márquez’s book and Balzac’s.” Carlos Fuentes bizarrely said that Asturias “shows profound signs of senility.” Juan García Ponce echoed Fuentes writing “It is not that Asturias speaks like that because he is senile; what happens is that he was born senile. He continued “Asturias’ opinions, like his books, are not the same as those of his readers, but rather the same as those of his readers, they are not worth it.” Behaving like a spoilt brat Gustavo Sainz writes that Asturias’s books “do not stand the test of a second reading; furthermore, these works no longer impress us as they did before; fifteen years ago they were the best, but now Latin America has wonderful writers like Cortázar, Fuentes and others who make Asturias look bad.”[12]

These writers are wrong in so many different ways that it would take a book to explain why. So, to finish this review of such a landmark book on more positive note I will leave that final words to the translator David Unger explaining why he will not be translating anymore of Asturias more complex books. “It’s important for a writer and a translator to recognize their limitations. I don’t think I have the skills to successfully render many of Asturias’s more complex and indigenous novels into English. It can be done, but not by me. If I have contributed to the reassessment of Asturias in the Anglo world, then I will be pleased. But I think I will stop here when I am, hopefully, ahead of the game—Claire Messud said in Harper’s that my translation was “brilliant.” I’ll Savor that compliment for now and evermore![13]

[1] https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/my-president-mario-vargas-llosa/

[2] Men of Maize Paperback – 10 Mar. 2025 by Miguel Ángel Asturias (Author), Héctor Tobar (Foreword), Gerald Martin (Introduction, Translator)

[3] https://keith-perspective.blogspot.com/search?q=david+unger

[4] A novel The CIA Spent a Fortune to Suppress- https://www.publicbooks.org/a-novel-the-cia-spent-a-fortune-to-suppress/

[5] https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2024/07/25/lmic-j25.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_American_Boom

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Congress_for_Cultural_Freedom

[8] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1967/asturias/lecture/

[9] A novel The CIA Spent a Fortune to Suppress- https://www.publicbooks.org/a-novel-the-cia-spent-a-fortune-to-suppress/

[10] Mr. President (Penguin Classics) Paperback – 12 July 2022

[11] https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-timely-return-of-a-dictator-novel

[12] https://www.milenio.com/cultura/laberinto/celos-miguel-angel-asturias-gabriel-garcia-marquez

[13] https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2022/07/14/death-hope-and-humor-david-unger-on-translating-miguel-angel-asturiass-mr-president/

Canción by Eduardo Halfon-Published by Bellevue Literary Press on September 20, 2022, 160 pages, $17.99 paperback

“Every writer of fiction is an imposter,”

Eduardo Halfon

“Literature is not about answers. But questions”:

Eduardo Halfon, Author of Canción

“We only found marbles, toys, coins, cooking utensils, sandals and flip-flops next to their bodies.”

Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team

“Life is not an easy matter…. You cannot live through it without falling into frustration and cynicism unless you have before you a great idea which raises you above personal misery, above weakness, above all kinds of perfidy and baseness.”

― Leon Trotsky, Diary in Exile, 1935

“Learning carries within itself certain dangers because out of necessity one has to learn from one's enemies.”

― Leon Trotsky, Literature and Revolution

Eduard Halfon’s novel just over 150 pages is written in the first person and contains autobiographical segments. It begins with the author visiting Tokyo for a conference to honour Lebanese writers. The innocent-sounding title of the book refers to a killer known for his not-so-pretty voice.

Halfon has a deceptively natural way of portraying the murderously complex social and political issues arising from the bitter civil war in Guatemala 1960-1996. Halfon’s prose is simple but exquisite. Canción like all of Halfon’s previous books Polish Boxer, Monastery, and Mourning is excellently translated from Spanish by Lisa Dillman and Daniel Hahn.

The book would appear to be meticulously researched and in a recent interview Halfon explains his methodology “When you’re writing a story that’s part of a historical account, that history must be believable. In the case of Canción, that means its historical background, the Guatemalan Civil War, and the country’s recent history. I needed to investigate all of that, and I felt like I had to include it more for the feeling than for the facts. Some details are in the background—they’re props, so to speak—and some details are part of the story.

That weaving is very organic, though. There’s no premeditation. It’s just a feeling of what should be where on the stage. What should be in the foreground? What should be in the background? It’s a very natural process of selection and placement. The research in books like Canción must be very methodical because I am trying to recreate a specific moment in time. So, newspapers, records, logbooks, accounts, the CIA file on my grandfather’s kidnapping—these were all available to me. Sometimes I need little details, but mostly I just need the prop of facts for the theatre to be believable. That is, for the atmosphere to be believable. I’m not interested in the facts, but in the smell and taste that the facts leave behind.”[1]

David L. Ulin writes “Like so much of Halfon’s writing, the narrative of “Canción” unfolds in an elusive middle ground where heritage becomes porous. For anyone familiar with his project, this will not come as a surprise. The author is a diasporic figure: Born in Guatemala City, raised there and in Florida and educated in North Carolina, he has lived in Europe and Nebraska. His metier is family: the way we are shaped by it and the way we push back on or move beyond it; how it both supports and limits us. In “The Polish Boxer” (2012), his first book to be translated into English, this leads him to consider his other grandfather, who survived Auschwitz with the help of a fighter who came from his village. “Mourning,” his most recent book, revolves in part around his uncle Salomon, whose drowning as a child resonates in “Canción” as well.”[2]

Like many of his generation of Guatemalan writers Halfon never witnessed first-hand the murderous civil war and faced the problem of how to write a book which includes historical facts and events he didn’t witness. As Halfon correctly says “Every writer of fiction is an imposter “. When he returned to Guatemala in 1993, he suffered persecution. Along with other writers and journalists, he was targeted by the government. Halfon often spoke of how he was followed and threatened in his own house after his first novel was published in 2004.

The treatment of writers and journalists by the Guatemalan state shows that the so-called peace accord brokered by the United Nations was nothing of the sort. The Guatemalan civil war was a social, economic and political disaster. Andrea Lobo writes “Nearly a quarter million people were killed between 1962 and 1996 in Guatemala, 93 percent at the hands of pro-government forces. The UN-backed Commission for Historical Clarification classified the massacre of Mayan Indians, treated by the military as a potential constituency for guerrillas, as genocide, including the destruction of up to 90 per cent of the Ixil-Mayan towns and the bombing of those fleeing.[3]

Halfon believes that not much has changed since 1996, He writes that “Certain things in Guatemala are simply not spoken or written about. The indigenous genocide in the 1980s. The extreme racism. The overwhelming number of women are being murdered. The impossibility of land reform and redistribution of wealth. The close ties between the government and the drug cartels. Although these are all subjects that almost define the country itself, they are only discussed and commented on in whispers, or from the outside. But a second and perhaps more dangerous consequence of a culture of silence is a type of self-censorship: when speaking or writing, one mustn’t say anything that puts oneself or one’s family in peril. The censoring becomes automatic and unconscious. Because the danger is very real. Although the days of dictators are now gone, the military is still powerful, and political and military murders are all too common”.[4]

Unfortunately, this will not change with the election of the new government of Bernardo Arévalo. Arevalo’s election was challenged by dominant sections of the Guatemalan capitalist oligarchy who sought to overturn his election through many legal cases alleging electoral fraud, illegal financing and other irregularities. All of which failed.

As Andrea Lobo writes “Arévalo is the son of the country’s first elected president, Juan José Arévalo (1945-1951), who remained within the left nationalist government of his successor Jacobo Arbenz when it was overthrown in a CIA-orchestrated military coup in 1954. A series of military-civilian dictatorships followed, crushing opposition from below to protect the interests of US capitalists and their local partners.

Cancion is well worth a read, as are his previous books. It remains to be seen if Halfon’s next novel reflects illusions that exist within left Guatemalan journalists and writers regarding the new Arevalo government.

[1] “Literature is not about answers. But questions”: An Interview with Eduardo Halfon, Author of Canción-//www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2022/10/12/literature-is-not-about-answers-but-questions-an-interview-with-eduardo-halfon-author-of-cancion/

[2] Review: How a Guatemalan kidnapping inspired Eduardo Halfon’s auto fictional ‘Cancion’ www.latimes.com

[3] wsws.org

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/books/the-writing-life-around-the-world-by-electric-literature/2015/nov/04/better-not-say-too-much-eduardo-halfon-on-literature-paranoia-and-leaving-guatemala

Interview with David Unger- Author of Jose Feeds the World

Q.How did you get involved in the project of José Feeds the World?

A. I’ve been friends with Mauricio Velázquez, the publisher of Duopress, for over 20 years. Mauricio is a Mexican national who has been living in the U.S. for maybe 25 years and worked previously as an editor for Rosen Publishers. In the fall of 2022, knowing of my previous children’s books, he asked me if I would be interested in writing a non-fiction book about Chef José Andrés. Since I was familiar with the chef and the amazing work of his World Central Kitchen, I jumped at the chance. Mauricio offered valuable editorial comments, but basically he allowed me to craft my own book. It has been an amazing experience.

Q. How different is writing a children's book than one with more adult themes.

A I published La Casita, my first children’s book in 2012, and I have published four other kid’s books since then. What you might not know, Keith, is that I have translated 8 children’s books, including three by Guatemalan Nobelist Rigoberta Menchú, for the Canadian publisher Groundwood Books. Through this translation work, I went through a kind of apprenticeship. Obviously writing children’s books requires a different skill set than writing adult fiction. In all my work, I have been interested in how characters adjust and change, and how experience transforms their lives—this obsession is imbedded in me…It also helps that I have three daughters and five grandchildren.

Q.What was the relationship between you and Marta? Did the illustrations come first or did the words.

A. I was familiar with the children’s books that Marta did for Source Books, now the parent company of Duopress. Her illustrations for the books The Girl Who Heard the Music, Dinosaur Lady and Shark Lady really impressed me: they are lyrical, expansive and very child oriented. I wrote the text and I was overjoyed when Mauricio said that Marta, who comes from a village close to Jose Andres’s birthplace, WANTED to illustrate my book, for obvious reasons. I am the beneficiary of her amazing talent.

Q. I can see on Facebook you have already taken the book into schools etc. How has it been received both in schools and in the media.

A.It has been a wonderful experience to present the book, primarily in book store presentations. There is nothing greater than feeling the enthusiasm of young readers—their responses are always uncensored and quite electric. Younger kids respond more to the illustrations, but 7- and 8-year-olds understand the narrative that Marta has illustrated and ask quite interesting questions.

Q.what are you working on now? Do you plan any more collaborations with Marta?

A.I have written a couple of other children’s book texts, but haven’t found a publisher. I would love to collaborate with Marta or with Marcela Calderón, the illustrator of my previous kid’s book called Topo pecoso/Moley Mole. Both are so talented, but publishers decide what is printed and who illustrates text.

José Feeds the World: How a Famous Chef Feeds Millions of People in Need Worldwide February 29 2024, by David Unger and illustrated by Marta Alvarez Miguéns.

David Unger’s new book is the true story of José

Andrés, an award-winning chef, food activist, and founder of World Central

Kitchen.[1]

This disaster relief organisation helps working-class communities when

catastrophe hits. Although primarily aimed at children,

adult readers learn much from Unger's understated and thoughtful text.

The book is beautifully illustrated by Marta Alvarez

Miguéns, a freelance illustrator based in La Coruña, Spain. Her previous works

have included A Tiger Called Tomás, Dinosaur Lady and Shark Lady, which was

named a Best STEM Book by the Children's Book Council and the National Science

Teachers Association.

Jose Andres and his organisation are very busy at the

moment. Every day, a new disaster, war, appears, coupled with the massive

growth of world poverty and hunger. According to The State of Food Security and

Nutrition in the World 2022, published by the Food and Agriculture Organization

(FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), the International Fund for Agricultural

Development (IFAD), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and World

Health Organization (WHO), have reported that up to 828 million people, nearly

11 per cent of the world’s population, faced hunger in 2022. The number has

grown by about 140 million since the start of the pandemic.

There is no doubt about Andres's sincerity and

bravery in alleviating world hunger and poverty, saying, “What we’ve been able

to do is weaponise empathy. Without empathy, nothing works.”.But the cruel reality

is that Andres's work is insufficient to defeat world hunger and poverty.

Jean Shaoul writes, “World leaders are acutely aware

of the repercussions of the spiralling cost of food as workers demand pay

increases and take to the streets in protest over their deteriorating living

conditions in rich and poor countries alike. But the fight for decent wages,

affordable food, necessities and a massive increase in wages means that the

working class must unite across workplaces, industries, countries and continents

in a global political struggle against the capitalist class and its governments

and to put an end to the imperialist war.”[2]

Harsh Times: A Novel, Mario Vargas Llosa; translated by Adrian Nathan West, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 304 pp., $28.00, November 2021

The ability to persuade us of ‘truth,’ ‘authenticity,’ and ‘sincerity’ never comes from the novel’s resemblance to or association with the real world we readers inhabit. It comes exclusively from the novel’s own being, from the words in which it is written and from the writer’s manipulation of space, time, and level of reality.

Mario Vargas Llosa

What is Art? First of all, Art is the cognition of life. Art is not the free play of fantasy, feelings and moods; Art is not the expression of merely the subjective sensations and experiences of the poet; Art is not assigned the goal of primarily awakening in the reader 'good feelings.' Like science, Art cognises life. Both Art and science have the same subject: life reality. But science analyses, Art synthesises; science is abstract, Art is concrete; science turns to the mind of man, Art to his sensual nature. Science cognises life with the help of concepts, Art with the aid of images in the form of living, sensual contemplation.

A.Voronsky-Art is the Cognition of Life

“Truth is found neither in the thesis nor the antithesis, but in an emergent synthesis which reconciles the two.”

― Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

“The owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the coming of the dusk.”

― Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Elements of the Philosophy of Right

Whether or not you agree with Noble laureate Mario Vargas Llosa’s political outlook, his novel Harsh Times about the Coup in 1950s Guatemala is a cracking read. According to Edward Docx, “It speaks to our times”. However, the general reader would do well to delve into the history books of this period, especially Guatemala's history, to fully appreciate the novel's power.

As Docx correctly states, “In many ways, he is the embodiment of what a great novelist should be: unafraid to write panoptic political novels about the fate of nations and the clash of political ideologies; intellectually capable of encompassing such scope; artistically skilful enough to suffuse it with resonance, torque and drama; and all of this without losing the immersive kinesis of individual stories taken from all points on the compass of the human character.”

Vargas Llosa stays very close to some facts, but not all of them. However, he manages to weave a path to the lives of real and fictional characters. Vargas is not a stranger to writing novels that include historical events in Latin America. His tendency to reduce the ideological battles of the Cold War to little more than a minor deviation of “a democratic ideal” is a dangerous simplification of complex historical processes and tends to downplay the role of U.S. imperialism in the tragic events in Guatemala. Perhaps more damaging is Vargas’s insistence that the novelist has no obligation to represent historical facts.

As Ivan Kenneally writes, “ In a lecture he delivered on his own, The Real Life of Alexandro Mayta, Vargas Llosa maintained that the novelist bears no responsibility to represent historical facts at all faithfully. The events as they truly transpired—to the extent that this can be objectively determined—furnish only the “raw materials” for the construction of a novel, the initial “point of departure,” a contention he emphatically espouses discussing another of his works, The War of the End of the World. The singular obligation of the novelist is to be persuasive, to imaginatively materialise a world that does not reproduce but rather negates the one normally inhabited by the reader, a substitution of such force it can induce joy, despair, and revelation. This “sleight of hand replacement of the concrete, objective world of life as it is lived with the subtle and ephemeral world of fiction” is the fulcrum of the novelistic enterprise. Its believability has nothing to do with a humble obeisance to fact. Still, it is a function of the “ponderous and complicated machinery that enables a fiction to create the illusion that it is true, to pretend to be alive”.

Llosa’s playing fast and loose with historical truth is dangerous and has political and historical consequences. His viewpoint is opposed by Kenneally who writes again “If the authoritative power of literature is disconnected from its relation to reality, then why write a historical novel at all? Why should the novelist not manumit himself from the “raw material” supplied by documented history? If the point is to enact the “illusion of autonomy,” the “impression of self-sufficiency, of being freed from real life,” why choose a genre that insistently invokes the irrepressibility of extra-literary existence?[1]

Like many of his generation Llosa began his early career somewhat sympathetic to the revolutionary left’s ideals. The glorification of revolutions such as the Cuban was not confined to a generation of Latin American intellectuals such as Llosa. Several petty-bourgeois radical groups, such as the Socialist Workers Party (U.K.) complemented them. Bert Deck writing in the International Socialist Review said “The Cuban revolution has shattered the old structure of radical politics in Latin America by providing a new example to follow. New currents and tendencies are emerging. Two roads present themselves to the Latin American revolutionists: “The Guatemalan Way” or “The Cuban Way.” Fidelismo, a more revolutionary alternative to the Communist parties, already exists. The possibility of avoiding the trap of popular front politics has been improved immeasurably. In this new, open situation, the Marxists have an unprecedented opportunity to win support for a consistent revolutionary program. In the complex process of political realignment within the workers movement lies the hope of avoiding future Guatemalas – the hope for a Socialist United States of Latin America.”[2]

The British Trotskyists from the Socialist Labour League opposed this political line saying “Even if Castro and his cadre were “converted” would that make the revolution a proletarian revolution? … If the Bolsheviks could not lead the revolution without a conscious working class support, can Castro do this? Quite apart from this, we have to evaluate political tendencies on a class basis, on the way they develop in struggle in relation to the movement of classes over long periods. A proletarian party, let alone a proletarian revolution, will not be born in any backward country by the conversion of petit-bourgeois nationalists who stumble “naturally” or “accidentally” upon the importance of the workers and peasants. The dominant imperialist policy-makers both in the USA and Britain recognise full well that only by handing over political “independence” to leaders of this kind, or accepting their victory over feudal elements like Farouk and Nuries-Said, can the stakes of international capital and the strategic alliances be preserved in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.[3]

Over time, politically, Llosa began shifting further to the right. During the 1980s, he became a champion of free markets and political liberalism, standing as a centre-right presidential candidate in the Peruvian presidential election in 1990. More recently, his rightward drift has become more open. In 2014, he joined the Mont Pelerin Society, the organisation founded by Friedrich Hayek in 1947 that has become famous for neoliberalism.[4]

Llosa’s sharp shift to the right coloured his analysis of the early Cold War period. He lamented that the C.I.A.-sponsored Coup against Arbenz had caused too many young people in Latin America to turn towards communism and that the United States had crushed “the liberal democratic aspirations” of the people.

His book faithfully reconstructs the events in Guatemala that began with the 1944 October Revolution and ended with the Coup in 1954. The election of Jacob Arbenz. Welcomed by many left-leaning media outlets who hoped that the election of the liberal Arbenz would bring about a new “democratic spring,” Arbenz’s election was met with uncontrollable rage by American Imperialism.

Even the so-called “democratic spring” under J.J. Arévalo and his successor Jacobo Arbenz, who, unlike Bernardo, came to power based upon a program of democratic, agricultural and social reforms, proved most fundamentally that there is no peaceful or reformist road for the masses in Guatemala and other semi-colonial countries to secure their democratic and social rights.

In 1954, the United States carried out a coup d’état to remove Guatemala’s President Jacobo Arbenz from power, cancelling land reforms. The elected government of Arbenz by introducing a limited agrarian reform that infringed upon the vast holdings of the politically influential United Fruit Company drew the wrath of U.S. Imperialism.

Dwight Eisenhower would later acknowledge, “We had to get rid of a Communist Government which had taken over.” Llosa, the book stops at the 1954 coup. The Coup led to decades of dictatorships, The subsequent Guatemalan elites murdered over 200,000 Guatemalans, most of whom came from the indigenous Mayans.

Eduardo Galeano characterised the decades of dictatorship that followed in his book Open Veins of Latin America: “The World Turned its Back while Guatemala underwent a long Saint Bartholomew’s night. [In 1967,] all the men of the village of Cajón del Rio were exterminated; those of Tituque had their intestines gouged out with knives; in Piedra Parada they were flayed alive; in Agua Blanca de Ipala they were burned alive after being shot in the legs. A rebellious peasant’s head was stuck on a pole in the centre of San Jorge’s plaza. In Cerro Gordo the eyes of Jaime Velázquez were filled with pins… In the cities, the doors of the doomed were marked with black crosses. Occupants were machine-gunned as they emerged, their bodies thrown into ravines.”

As Hegel said, “An idea is always a generalisation, and generalisation is a property of thinking. To generalise means to think”. Whatever its faults and many, Llosa’s new book certainly makes you think, and it does “ speak to our times”. It is perhaps an irony of history when the latest election occurred in Guatemala this year. Bernardo Arévalo, a candidate promoted by the pseudo-left and U.S. imperialism, won the election. Juan José Averalo's son Arevalo was president after the 1944 October Revolution. There is absolutely no basis for describing Arévalo as a left, democratic or progressive alternative to the clientelism of Guatemala’s ruling elite, whose subordination to foreign capital and U.S. imperialism is the main cause of the rampant poverty, inequality, authoritarianism and corruption that characterise Guatemalan social life.

[1]Mario Vargas Llosa: Harsh Times and the “Fantastical Repudiation of Reality”

March 10, 2022 Ivan Kenneally-https://openlettersreview.com/posts/mario-vargas-llosa-harsh-times-and-the-fantastical-repudiation-of-reality

[2] Guatemala 1954 – The Lesson Cuba Learned: International Socialist Review, Vol.22 No.2, Spring 1961, pp.53-56.

[3] Letter of the NEC of the Socialist Labour League to the National Committee of the Socialist Workers Party, May 8, 1961 – Trotskyism versus Revisionism, Volume 3.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mont_Pelerin_Society

Interview With Guatemalan Writer David Unger

“Brought up between three cultures and two languages, David Unger has managed to capture with much irony and passion the trials and tribulations of a Jewish family in 1980s Guatemala. The story of three brothers, of the shocks between civilizations that are so in vogue these days, and of the plurality of cultures that coexist in Latin America, Life in the Damn Tropics is a novel that one reads with much perplexity and immense pleasure.”

— Jorge Volpi, author of In Search of Klingsor

"In The Mastermind, David Unger’s compelling antihero reminds us of the effects of privilege and corruption, and how that deadly combo can spill from the public to the private sphere. Unger’s Guillermo Rosensweig is on a hallucinatory journey in which everything seems to go right until it goes terribly, terribly wrong. I couldn’t put this down."

--Achy Obejas, author of Ruins

1 How did the possibility of translating the new book come about?

In 2016, I published my most recent novel, The Mastermind (New York: Akashic Books), which is based rather loosely on real events that caused an existential crisis in Guatemala and almost brought down a left-of-centre government in 2009. It’s a book that has been translated into ten languages. At the time, I felt that I wanted to give back to my birthplace in a unique way. Over the years, I’ve translated 16 books, so it seemed that I should attempt to re-translate Guatemala's Nobel prize in literature author Miguel Angel Asturias’s first and most powerful novel. I contacted the Balcell’s Agency which gave me the green light, but due to some copyright issues, I had to wait until 2022 to publish my translation of Mr. President with Penguin Classics.

2. What do you think of the previous translation by Frances Partridge? What problems were involved after the last translation was over fifty years ago?