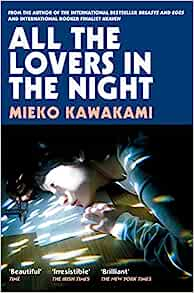

All the Lovers in the Night, Mieko Kawakami, Sam Bett (trans), David Boyd (trans) (Europa Editions, Picador, May 2022)

“In my chair, I surrendered myself to a world of sound that could only be described as sparkling. It made my head sway, and my breath grew deeper as my legs climbed up that evanescent staircase, each step a sheet of light. They would shimmer to life the second my sole made contact, then fizzle into stardust when I lifted my foot, only to be reborn as yet another step, gently showing me the way.”

All the Lovers in the Night

‘I want to write about real people,’

Mieko Kawakami

“There are just as many memories as there are people, so there’s no correct version of one event. That’s why we need many different kinds of voices and experiences, and by reading those voices, we understand and construct a bigger picture of the world.”

Mieko Kawakami.

“Those Who Fight Most Energetically and Persistently for the New Are Those Who Suffer Most from the Old”

Leon Trotsky

All the Lovers In the Night is Mieko Kawakami’s third novel. The book covers similar ground to her previous books, " Breasts and Eggs and Heaven. All three books were translated into English by Sam Bett and David Boyd, with Breasts and Eggs having sold over 250,000 copies in thirty countries. Kawakami’s novels have come under sustained criticism from Japanese conservatives, Shintaro Ishihara, Tokyo’s former governor and a former novelist, called them “unpleasant and intolerable”.

Mieko Kawakami is one of the most important writers to come out of Japan. Kawakami was born in Osaka in 1976. Her family were working class and poor. She was forced to work in a factory at the age of making heaters and electric fans. Later she had a job as a hostess and a singing career, finally becoming a blogger and a poet. She has almost single-handily dragged Japanese literature into the 21st century. She won many awards, including the Akutagawa Prize, in 2008. Haruki Murakami, one of the most important Japanese novelists, praised the writer, saying Kawakami is “always ceaselessly growing and evolving.” However, Kawakami has not always liked Murakami's portrayal of women.[1] In a 2017 interview with Murakami, she opposed his perceived sexism, saying, “I’m talking about the large number of female characters who exist solely to fulfil a sexual function” and “Women are no longer content to shut up,”

All the Lovers in the Night covers the life of a working-class Japanese girl, Fuyuko Irie, a proofreader in Tokyo. Fuyuko is a typical character used by Kawakami, a person who is single, childless, largely a loner and travels through life unnoticed and unloved.

As Fuyuko Irie says, “What I saw in the reflection was myself, in a cardigan and faded jeans, at the age of thirty-four. Just a miserable woman who couldn’t even enjoy herself on a gorgeous day like this, on her own in the city, desperately hugging a bag full to bursting with the kind of things that other people wave off or throw in the trash the first chance they get.”

There is cleverness in how “All the Lovers in the Night” addresses all the changes in the book's main protagonists. Kawakami never judges her characters and empathises with them/. As Joshua Krook writes, “If there is a core question in Kawakami’s work, it is what the oppressed should do to feel okay with themselves. Most of her stories feature people who are ignored or mistreated by society, with many having psychological problems stemming from their mistreatment. The protagonists cling onto one or two people as lifelines that keep them afloat in the storm.”[2]

Kawakami’s Treatment of Irie’s alcoholism is particularly sensitive. Alcoholism seems to be a major problem in Japanese society. Just typing in Google search engine for alcoholism amongst young Japanese women brings up many articles.

A recent study found that “young Japanese people drink much more alcohol than the global average. In 2020, 73 per cent of men aged 15 to 39 in Japan drank harmful amounts of alcohol compared to 39 per cent of their male peers globally. The difference was even starker for Japanese women: 62 per cent of women aged 15 to 39 years in Japan drank harmful amounts of alcohol in 2020 compared to just 13 per cent of young women globally.”[3]

Kawakami is not shy about discussing subjects barely mentioned in Japanese or, come to that matter, in Western Society, such as social class and gender. Her treatment of sexual violence towards women is one such issue. As Cameron Bassindale writes in his book review, “It reaches a nadir in tone when Kawakami produces a chapter detailing sexual violence which is so visceral and believable it will leave those weak of temperament wondering why they ever picked up this book. That is to say, Kawakami has truly outdone herself, surpassing even her lofty expectations of creating a narrative which is immediate and realistic; this English translation is a gift to anyone wishing to understand life for the modern Japanese woman and the perils and hardships many women face. Of course, no two human experiences are the same, and that point is apparent in the contrast between the female characters in the novel; however, the space between men and women in the book tells the state of gender relations in Japan. It is up to the reader to draw their conclusions.”[4]

Several middle-class reviewers like Mia Levitan have sought to position Kawakami as some “literary feminist icon”. Levitan writes, “ Anti-heroines aching for erasure may point to a broader unease. Kyle Chayka, the author of The Longing For Less (2020), posits that a modern desire for nothingness stems from overstimulation. Or it may be a reaction to “girl-boss” feminism. “Instead of forcing optimism and self-love down our throats . . . I think feminism should acknowledge that being a girl in this world is hard,” suggests Audrey Wollen, the Los Angeles-based artist who became known in 2014 for her “Sad Girl Theory”, which reframes sadness as a form of protest.”

A turn towards feminism cannot solve the problems women face in Kawakami's books or in real life. The plight of working-class women in Japan or anywhere else is inseparably linked to the plight of the working class.

As Kate Randall correctly points out, “The fight for women’s rights is a social question that must be resolved in the arena of class struggle.As Rosa Luxemburg once explained: “The women of the property-owning class will always fanatically defend the exploitation and enslavement of the working people, by which they indirectly receive the means for their socially useless existence.”[5]

All the Lovers in the Night is well-written, eminently readable, and sometimes beautiful. Although largely written about womanhood, it is still a great novel, and one looks forward to Kawakami’s future work.

[1] A Feminist Critique of Murakami Novels, With Murakami Himself- https://lithub.com/a-feminist-critique-of-murakami-novels-with-murakami-himself/

[2] https://newintrigue.com/2021/06/18/the-writing-of-mieko-kawakami/

[3] Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020- www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)00847-9/fulltext

[4] bookmarks.reviews/reviewer/cameron-bassindale/

[5] The condition of working-class women on Internation

Terminal Boredom: Stories, Izumi Suzuki, Polly Barton (trans), Sam Bett (trans), David Boyd (trans), Daniel Joseph (trans) (Verso, April 2021)

" Men loom large in many of Suzuki's stories as a potential threat. "Women and Women" is the most extreme example. Men once ruled society "through violence and cunning" but are now relegated to an exclusion zone where their only purpose is to help women conceive.

'There is something wrong with our present society, and I can't stand SF written by people who don't understand that,'

Izumi Suzuki

“In every society the degree of female emancipation (freedom) is the natural measure of emancipation in general.”

Charles Fourier

"The followers of historical materialism reject the existence of a special woman question separate from the general social question of our day. Specific economic factors were behind the subordination of women; natural qualities have been a secondary factor in this process. Only the complete disappearance of these factors, only the evolution of those forces which at some point in the past gave rise to the subjection of women, is able in a fundamental way to influence and change their social position. In other words, women can become truly free and equal only in a world organised along new social and productive lines."

Alexandra Kollontai

The stories collected in Terminal Boredom address many issues currently in vogue. Suzuki's use of classifications, such as gender and identity politics rather than class, is music to the ears of the new #MeToo movement. This petty-bourgeois layer will no doubt receive her book with open arms. The movement must be running out of steam if it decides to resurrect an author who died more than three decades ago.

Rather than being translated by one person, her stories are done by six, Daniel Joseph, David Boyd, Sam Bett, Helen O'Horan, Aiko Masubuchi, and Polly Barton. It is above my pay grade to say whether this works, which seems fine.

Suzuki was active as a writer in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Although not a writer of the "Lost Decade",[1] Suzuki's writing was deeply influenced by the Japan that emerged after the Second World War. As Peter Symonds writes, "The restabilisation of Japanese capitalism after World War II under the US occupation depended on the crushing of the resurgent working class, above all through the betrayals of the Japanese Communist Party (JCP). The post-war constitution drawn up by the American occupiers was designed to appease widespread public hostility to the wartime militarist regime and ensure Japan would not return to war against the US. But the LDP, which ruled Japan almost continuously from 1955 to 2009, never broke from the militarist past and has long harboured ambitions to restore wartime "traditions".[2]

The suppression of the Japanese working class harmed Suzuki's worldview. Rejecting the working class as an agent of revolutionary change, Suziki sought out middle-class forces to bring about change in Japanese society, saying, 'There is something wrong with our present society, and I can't stand SF written by people who don't understand that”.

As Ian MacAllen writes, "Science fiction dystopias are often deployed as a means of examining politics, ideology, or technology, but for Izumi Suzuki, the medium serves as an intimate exploration of anxiety, pain, and sadness. The translated stories collected in Terminal Boredom depend on science fiction dystopias but focus on characters who are broken and seeking their own personal redemption rather than the expected grand narratives about society as a whole. Even though sometimes they are "out of this world" aliens or living in reimagined societies of the future, these are people struggling in the same ways we struggle today."[3]

There is nothing progressive about her worldview. Her short story "Women and Women " is about men confined to a concentration camp and used only for procreation and women's satisfaction. Suzuki has been compared to writers like Phillip K Dick, who, according to James Brookfield, "was a prolific writer who completed 44 novels and roughly 121 short stories before his untimely death from a stroke in 1982 at age 53—was imaginatively gifted in posing large questions. What would people do if the fascists had prevailed? How would society be altered by the eventual development of robots sufficiently advanced to pass as humans? (The latter being the premise of his 1968 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? which served as the basis for the 1982 Ridley Scott film Bladerunner). Other stories by Dick were adapted for the films Minority Report (2002) and The Adjustment Bureau (2011).[4] This comparison is a disservice to Dick, who compared Suzuki was a far more intelligent and progressive writer.

While all great writers draw upon personal experiences, Suzuki's work is filled with deep melancholy and sadness, which is hardly surprising given her upbringing. Born in 1949, she took her own life at just thirty-six. She found fame as a model and actress before becoming a writer. she worked with the controversial photographer Nobuyoshi Araki and directors Shūji Terayama and Kōji Wakamatsu. In 1973 she married the jazz saxophonist Kaoru Abe, with whom she had a daughter. Ending in divorce in 1977. Her ex-husband died from an accidental overdose of Bromisoval in 1978. The relationship was stormy, and she cut off one of her toes in front of her husband.

While the Metoo movement has hailed her as one of her own, Suzuki was not completely defined by her sex. Her feminism was a complex phenomenon. As Daniel Joseph writes, “Suzuki's relationship to gender and feminism is complex and nuanced, requiring the twenty-first-century reader to step outside of hard-line contemporary rhetoric. But while a contemporary mode of feminism may not be overtly apparent in her work, Suzuki often spoke out against the unrealistic feminine ideals imposed upon women by male SF authors in the form of beautiful, cookie-cutter female characters. She also dismissed essentialist stereotypes like 'women's intuition' and demanded the right to be a real, flawed human being. Kotani again: 'Suzuki's texts defamiliarise the real world to demolish and reconstruct the "femininity" bound hand and foot by real-world power structures. Her works dismantle the power structures whereby women are marginalised through phrases like "only a woman would…" or "because she is a woman." It is only through this process that one can begin to think about what constitutes "femininity."' But even at her most political, Suzuki is never polemical. She approaches such questions obliquely, attacking imperialism ('Forgotten') and casually dismissing gender as a social construct ('Night Picnic', 1981) while depicting troubled romance and the absurdities of family life. Meaning flows through her stories like music, and despite the obvious complexities of her work, Suzuki described her writing in simple terms: 'I turn my dreams into stories'.”[5]

I cannot bring myself to recommend this book. All one can hope for is that the next book of Suzuki’s work to be published by Verso will be a little better.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost_Decades

[2] The revival of Japanese militarism-www.wsws.org/en/articles/2013/08/03/pers-a03.html

[3] chireviewofbooks.com/2021/04/21/terminal-bordom-izumi-suzuki/

[4] If Nazism had prevailed: The Amazon series The Man in the High Castle- https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2020/04/21/high-a21.html

[5] How Izumi Suzuki Broke Science Fiction’s Boys’ Club- https://artreview.com/how-izumi-suzuki-broke-science-fiction-boys-club/

Breasts and Eggs-by Mieko Kawakami, translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd-Europa, 430 pp., $27.00; $16.95 (paper)

"I guess she was one of those people you see a lot these days who looked young from behind, but the second that she turned around…. Her fake teeth were noticeably yellow, and the metal made her gums look black. Her faded perm had thinned so much that you could see the perspiration on her scalp. She was wearing way too much foundation. It made her face look washed out and more wrinkly than it was. When she laughed, the sinews of her neck popped out. Her sunken eyes called attention to their sockets."

Breasts and Eggs

'Women are no longer content to shut up'

Mieko Kawakami

"the dominant view today is that women have always been to some degree oppressed—the usual term is "dominated"—by men because men are stronger, they are responsible for fighting, and it is in their nature to be more aggressive. Common among those who discuss sex roles are blunt judgments, empirically phrased, that casually relegate to the wastebasket of history".

F Engels

Reading Mieko Kawakami's novel Breasts and Eggs, one concludes that it is not easy being a working-class woman in any country at the moment. Described as a Feminist, Kawakami seems more interested in describing the human condition rather than being saddled with this unsatisfactory label.

Her opposition to being called a Feminist writer has not stopped numerous people from labelling her so and a fighter against male domination. While God forbid that she stops writing the way she does, it would improve her writing if she imbued her characters with a little historical perspective. After all, men's relationship with women has been around for a long time and is a complex issue. While she would be met with hails of derision from her Feminist readers, she could do no worse than consult Friedrich Engel's extraordinary book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Engels writes eloquently, "the dominant view today is that women have always been to some degree oppressed—the usual term is "dominated"—by men, because men are stronger, they are responsible for fighting, and it is in their nature to be more aggressive. Common among those who discuss sex roles are blunt judgments, empirically phrased, that casually relegate to the wastebasket of history the profound questions about women's status that were raised by nineteenth-century writers. "It is common sociological truth that in all societies authority is held by men, not women," writes Beidelman; "At both primitive and advanced levels, men regularly tend to dominate women," states Goldschmidt; "Men have always been politically and economically dominant over women," reports Harris. Some women join in. Women's work is always "private," while "roles within the public sphere are the province of men," writes Hammond and Jablow. Therefore "women can exert influence outside the family only indirectly through their influence on their kinsmen".

The first problem with such statements is their lack of historical perspective. To generalise from cross-cultural data gathered almost wholly in the twentieth century is to ignore changes that have been taking place for anywhere up to five hundred years as a result of involvement, first with European mercantilism, then with full-scale colonialism and imperialism. Indeed, there is almost a kind of racism involved, an assumption that the cultures of Third World peoples have virtually stood still until destroyed by the recent mushrooming of urban industrialism. Certainly, one of the most consistent and widely documented changes during the colonial period was a decline in the status of women relative to men. The causes were partly indirect, as the introduction of wage labour for men, and the trade of basic commodities, speeded up processes whereby tribal collectives were breaking up into individual family units, in which women and children were becoming economically dependent on single men. The process was aided by the formal allocation to men of whatever public authority and legal right of ownership was allowed in colonial situations, by missionary teachings, and by the persistence of Europeans in dealing with men as the holders of all formal authority. The second problem with statements like the above is largely a theoretical one. The common use of some polar dimension to assess woman's position and to find that everywhere men are "dominant" and hold authority over women not only ignores the World's history but transmutes the totality of tribal decision-making structures (as we try to reconstruct them) into the power terms of our society.[1]

|

| Mieko Kawakami |

Breasts and Eggs is Kawakami's first full-length novel for English-language readers. This novel takes its characters and setting from a short novella published in 2008 and was awarded Japan's prestigious Akutagawa Prize. This book, it must be said, is not an easy read. The novelist and politician Shintaro Ishihara described Breasts and Eggs as "unpleasant and intolerable". This statement, however, can be taken in many ways.

While it is perhaps unusual for two people to translate a book, it is beautifully done by Sam Bett and David Boyd. However, they have faced criticism for moving away from the essence of Kawakami's use of the Osaka dialect, Which reinforces the working class nature of her characters. The dispute over their translation is above my pay grade, so I will leave it to others to argue the merit.

Madeleine Thien writes in her review, "the real Osaka dialect is not even about communicating. It is a contest. How can I put it? It's an art" – translators Bett and Boyd do not render it. In 2012, an excerpt of Breasts and Eggs was published by another translator, Louise Heal Kawai, who offers Makiko's "I've been thinking about getting breast implants" as "Natsuko, I am thinking of getting me boobs done". Kawai compares the Osaka dialect to Mancunian: rough, friendly, outspoken. In Bett and Boyd's translation, Kawakami's feminism is vivid, but the language occasionally feels placid; meanwhile, in Kawai's translation, feminism and language collide in a way that feels deliciously irreverent. Here is Brett and Boyd, translating Midoriko's response to her mother's desire for surgery: "It's gross, I really don't understand. It's so, so, so, so, so, so gross … She's being an idiot, the biggest idiot." Here is Kawai: "I don't get it. PUKE PUKE PUKE PUKE PUKE! … She's off her trolley, my Mum, daft, barmy, bonkers, thick as two short planks."[2]

To what extent this is an autobiographical piece will be known only to some extent by the author. Maybe women will have a closer bond with the characters in the book, but as a man, the plight of the women in the book also forces the male reader to confront their past and how they fit into the modern-day World.

The book's narrator represents a new generation of Japanese women who, while rejecting much of Japanese cultural, social and political norms, have yet to strike out in a new direction. Sarah Chihaya writes, "The idea that a woman, or anyone for that matter, might be able to articulate and lay claim to exactly what they want is laughably unsuited to these uncertain times. So what kinds of novels can be written about women who may not want anything from a world that may not have anything to offer them?".[3]

The book is divided into two parts, Breasts and Eggs. I am not inclined to separate the book into parts. The book deals with many problems of everyday life. Kawakami's first chapter is titled "Are You Poor?". It must be said that Kawakami is one of the few writers addressing the problems faced by working-class women in society. Her work cuts across the money-grabbing women of the #MeToo movement

The main character in the book is largely unconcerned with desirability, romance, or sexual pleasure but has yet to find a replacement for these basic social mores. She is not content with putting up with how she has been treated in the past but has yet to formulate a social or political way forward. One feels this novel is closer to the author's life than she may let on. The intensity of this study of Japanese working-class women forces both male and female readers to re-examine their own lives.

Kawakami is a precise and razor-sharp writer who discusses complex and sensitive subjects honestly and sensitively. She is a keen observer of the problems faced by working-class women. As this brutally honest depiction of one of the characters in the book shows, "Natsu sees everything and everyone she encounters, including herself; its dryness saps the poignancy from statements like "She reminded me of Mom." It is not that Natsu is devoid of emotion—her sadness at the earlier loss of her beloved grandmother is apparent throughout the novel. Yet that sadness, and her loneliness and estrangement, do not lead to yearning or desire. Mothers and grandmothers haunt all of the women in this novel, not just Natsu and Maki, but their ghosts do not emit the glow of family romance. Rather, the spectral presences are reminders of the accumulating malaise of the female body as it participates, willingly or unwillingly, in the mingled economies of labour and sexual desire—as one of Natsu's not-quite-friends unforgettably declares, their mothers and their mothers before them were just "free labour with a pussy." While a powerful bond of love joins these successive generations, it is a luxury that contemporary women's schedules cannot often afford".

One can see why the novel was harshly criticised in some conservative quarters because it exposes the horrendous plight of working-class women in Japanese society that treats them as second-class citizens.

As Vrinda Nabar writes, "It is easy to understand the outrage caused by Breasts and Eggs among a section of readers in Japan. Published in a newly expanded form in English translation in April this year, the novel's titillating title belies its upfront focus on themes that have less to do with female anatomy and more with the ways many women have quietly subverted gender roles. The discursive style allows its narrator Natsuko Natsume (a blogger nobody reads), to touch on several aspects of a single woman's life in Tokyo".[4]

Like all good writers, Kawakami draws heavily on her own experiences as a woman in modern Japan. However, there is nothing parochial about her work as she discusses universal themes of loneliness and sexuality in capitalist society. Her novels have struck a chord with hundreds of thousands of her readers. I highly recommend this book and cannot wait to read and review her new book. [5]

[1] https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/5128-engels-and-the-history-of-women-s-oppression

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/sep/11/breasts-and-eggs-by-mieko-kawakami-review-an-interrogation-of-the-female-condition

[3] https://www.pressreader.com/usa/the-new-york-review-of-books/20210429/281573768498656

[4] https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/review-breasts-and-eggs-a-novel-by-mieko-kawakami/story-gu4VLuf12Xofl726VXpTgM.html

[5] All The Lovers in the Night-Picador 2022

Heaven: A Novel by Mieko Kawakami-Translator: Sam Bett and David Boyd-New York. Europa Editions. 2021. 192 pages.

"Whom do I hate most among the rabble of today? The socialist rabble, the chandala apostles, who undermine the instinct, the pleasure, the worker's sense of satisfaction with his small existence—who make him envious, who teach him revenge. The source of wrong is never unequal rights but the claim of "equal" rights"—Nietzsche's The Anti-Christ, 1888

"I was always quite a philosophical child, asking odd questions and in a hurry to grow up". Mieko Kawakami

"'Progress' is a modern idea, which is to say it is a false idea."—Nietzsche's The Anti-Christ, 1888

Mieko Kawakami latest novel, excellently translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd, is a brutal examination of adolescence in Japanese society. The book is drawn from her childhood in Osaka, Japan. By all accounts, it was a pretty bad experience. Her father was never home. Forced into being the main breadwinner at a tender age to support her family gave her the ability to write this "novel of ideas" ". As Kawakami says, "I was always quite a philosophical child, asking odd questions and in a hurry to grow up".

Kawakami started to write at a very early age. She explains that "I try to write from the child's perspective—how they see the world. Coming to the realisation you are alive is such a shock. One day, we are thrown into life without warning."

In an interview with The Japan Times, Kawakami says, "I wanted to create a story that examines how religion, ethics and friendship influence human relationships," she says. "Do we live our lives under the guidance of something bigger, like spiritual or ethical beliefs, or do we live as individuals?".[1]

As Elaine Margolin perceptively writes, "Kawakami is captivated by that precious time of life when one is on the cusp of adulthood but still really a child. The author's ability to mimic the rhythmic disturbances of a teenage mind is mesmerising; she is a master of the interior voice. She instinctively grasps how one can feel silly and light one moment and be in the throes of anguish the next. In one of her earlier novels, Ms Ice Sandwich, she describes a lonely boy whose family is in disarray, finding solace by visiting a supermarket worker each day who kindly gives him an egg sandwich".[2]

The book's theme of childhood bullying is a universal one. " Kawakami explains that the nature of bullying has changed. "In the old days, there were just two places for relationships — home or school — but now, with social media, there is nowhere to hide, and the pressure is constant. Victims of bullying think the whole world knows they are being bullied. It is even crueller today with the way it can be spread."

I still remember my childhood bully. His name was Desmond Kavanagh. His reign of terror did not last too long. Unlike Kawamaki's character, who does not fight back, one person in my school had enough of Kavanagh's bullying and kicked the crap out of him. The bizarre thing is that Kavanagh tried to befriend me on Friends Reunited a few years later.

Novel of Ideas

Heaven has been described as a novel about ideas. Writing a "novel of Ideas" is a complicated business. Kawakami draws heavily on the work of philosophers like Frederich Nietzsche and Kant. A blog that she started to promote her singing career, "Critique of Pure Sadness," displayed an unhealthy fascination with Kant. Her latest book leans heavily on Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra. This is a very unfortunate choice, especially for such a young writer. Nietzsche's hostility towards the working class and socialism and his disdain for objective truth made him a favourite writer of the Nazi movement.

As Stefan Steinberg states, "Apologists for Nietzsche seek to distance him from the policy and activities of the Nazis. But is Nietzsche's position here so remote from Adolph Hitler's entreaty, in an internal NSDAP memo of 1922, for the: "most uncompromising and brutal determination to destroy and liquidate Marxism"? Adolph Hitler was certainly no philosopher, just as Nietzsche was not merely a political ideologue. But who can reasonably doubt that the former had little difficulty in seamlessly incorporating the latter's thoroughly backwards-looking programme of biological racism, hatred of socialism and the concept of social equality—together with his advocacy of militarism and war—into the eclectic baggage of ideas which constituted the programme of National Socialism"?.[3]

The strength of the novel is Kawamaki's examination of ideas as a way of writing a novel. As Merve Emre writes, "dreamlike expression of their fledgling ideas has an artistic value that flies in the face of critics like Northrop Frye, who believed that an "interest in ideas and theoretical statements is alien to the genius of the novel proper, where the technical problem is to dissolve all theory into personal relationships." But "Heaven" also models a rigorous and elegant process of inquiry that can transcend its pared-down fictional world. It agitates against the enduring idea that the best novels concern themselves with the singular minds and manners of people, offering no resources for the political and moral demands of "real life." The narrator's persecutor Ninomiya energetically parrots this argument".[4]

Kawakami, ability to write from a child's perspective is astonishing at times and avoids what one writer says are "puffed-up platitudes about the inherent cruelty and sympathy of children".

If I am generous, I would say that Kawakami also avoids Nietzsche's social and political pessimism and presents the world of children accurately. One major criticism is that, unlike many great Japanese writers, such as Yukio Mishima and Kazuo Ishiguro, she does not place her characters in this book in a social or political context. The reader would not know that while "Heaven" takes place in Japan, bullying is rife in Japanese society so much that classroom harassment forced a government to bring in national legislation because of a growing number of student suicides.

To conclude, Kawakami's work is well worth reading. Her fiction deals with the problems of everyday life for working-class people in Japan. That is one of the reasons behind her popularity. She examines critical social issues that permeate Japanese society. These include broken families, absent fathers and children struggling to find themselves in a increasingly cruel world. It is hoped that she does not spend too much time absorbing Nietzsche's works and instead let herself be influenced by some more healthy writers such as Thomas Mann and Hermann Hesse. She has a bright future, and I look forward to her next novel.

Mieko Kawakami is the author of the novel Breasts and Eggs, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and one of TIME's Best 10 Books of 2020. She was born in Osaka. Kawakami made her writing debut as a poet in 2006 and published her first novella, My Ego, My Teeth, and the World, in 2007. Her writing is deeply imbued with poetic qualities. Her work concentrates on the plight of women in Japanese society. Her works have been translated into many languages and are available all over the world. She has received numerous prestigious literary awards in Japan for her work, including the Akutagawa Prize, the Tanizaki Prize, and the Murasaki Shikibu Prize.

[1] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2021/05/27/books/heaven-mieko-kawakami/

[2]https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org/2021/spring/heaven-novel-mieko-kawakami

[3] https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2000/10/niet-o21.html

[4] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/06/07/a-japanese-novelists-tale-of-bullying-and-nietzsche