In the

author’s eye, wage labour stands for that descent into the proletarization of

people and communities, their systemic impoverishment through the appropriation

of their labour time, amounting to civil wars and overall societal unrest. Readers

may recall that Moore’s stated objective from writing the novel has been her

attempt to specify the reasons that lead to Liberia’s civil war (1989-1997)

during which she, a toddler (born in 1985), and her family were forced to flee

the country and settle in the US. It is worth recalling that Liberia is the

first nation-state in Africa. Its independence dates back to 1847, well before

countries such as South Africa, Egypt or even Ethiopia. But the country has remained

largely unstable and the advantage of Moore’s novel is that it promises to take

its reader to the motoring principle behind that instability and violence, that

is, to the foundation of wage labour system.

Moore’s

early attempts in fiction writing is a children book titled: I Love Liberia

(2011). She similarly champions a non-profit business adventure called ‘One

Moore Book’. Note the pun in ‘Moore’, highlighting both the word ‘more’ and the

author’s last name. The project aims at circulating “… culturally relevant

books to children who are underrepresented and live in countries with low

literacy rates.”(1) Besides, Moore’s faith in the

universal extension of knowledge to unfortunate young minds underscores her

initial cause of dispelling illusions and falsehoods, including those that have

put Liberia on the road of misery, impoverishment and interminable wars.

Several

observers and experts will keep reiterating that behind that generalized instability

and descent into bloody civil wars lies the same people’s backwardness,

incapacity to found an enduring social contract and endemic divisions between multiple

social components. All these factors should perhaps be approached with a grain

of salt because the listed ‘reasons’ subscribe more to the logics of

justification, not explanations. Indeed, such arguments are culturalist in

nature and all they succeed in achieving is to blame the victims and, in the

meanwhile, lift the blame from the real harm-inflictors, both people and structures.

The present essay underscores the need to consider the author’s approach and

setting of the story, since taking that into consideration, I claim, can be

conducive to register exactly what happened, and the way in which what indeed

happened (not that which is fancied as what happened) had ushered in in the

long term the civil war of the 1990s.

The

differential between that which indeed happened and that which portends to have

happened is a historiography that promises to propagate towards universal

emancipation. Leaving that which triggered the author’s own exile unexamined is

to remain stuck in superficialities-sold-as-histories, with the cost of

ensuring that cycles of violence will not only keep emerging but those cycles’

rhythm will have to be confronted with a telling regularity.

Before

detailing on wage labor, there exists the need to broach first on several

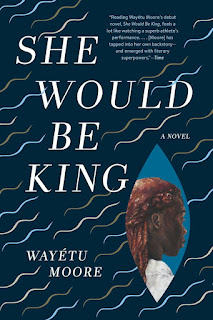

social players of modern Liberia as traced by the author in She Would be

King. We find at least two main components:

the first is the Vai and other indigenous communities as represented by Gbessa’s

story in the early part of the novel, offering a window into precolonial life in

an African village before European intrusion. Through the stigmatization of

Gbessa on the ground of her ‘ill-fated’ birth date, Moore illustrates that

precolonial life, that is, well before the incursion of European powers into

the continent’s interiors, life in Africa was far from being either idyllic or perfect.

Readers find that Gbessa is cursed simply because her birth date coincides with

an event interpreted as a bad omen. Through no fault of her own, and at the age

of eight, Gbessa is sentenced to die by abandoning her in the deep jungle. Her

parents are ostracized for bringing a child on a ‘wrong’ day, overlooking how

the wrong day is wrong only in the calendar of alienation!

The second category

of social actors are returnees, victims of slavery but who found themselves

obliged (like June Dey) or entreated (like Norman Aragon) to return and find

peace in Monrovia. Let us recall that these last two characters are themselves descendants

of enslaved Africans who do not necessarily come from Libera, or even nearby

localities such as the Ivory Coast or Ghana. Throughout the decades and even

the centuries, the first enslaved people died and their enslaved descendants

simply retained “Africa” or its idea less as their place of origin and more as a

place where they used to be free, their humanity round and unquestioned. It

should be noted that places such as Cameroon, Nigeria, Tanzania or the Congo

are recent inventions that come with colonial expansionist plans and labels

since by the time chattel slavery become generalized, these appellations (not

places) simply did not exist.

In She

Would be King, we find this affinity with Africa, less as a geographical

space or biological affiliation and more as an existential attachment to a promise

for emancipation with Nanni, Norman’s mother. Despite having the choice to live

among several Maroon communities in Jamaica, Nanni always feeds Norman, her son,

the obligation to leave Jamaica and to re-join Africa. To seize on her steadfastness

in bonding with Africa, readers cannot miss how she endures Callum’s pseudo-scientific

whims, slavery and even rape, all for the sake of earning a boarding passage to

Africa. Africa, she seizes, is both the physical territory and mental space

conceptualized as existential freedom, a radical breach with the reductionism

of one’s humanity that underlies her life as a slave. Nanni, Norman and June

Dey, as elaborated below, are Pan-Africanists avant la lettre. Well

before the foundation of the early to mid-twentieth century movement of

Pan-Africanism, we read that slaves in the Americas entertained not only exalted

dreams but elaborate plans to equally find and found freedom in Africa. Alternatively,

freedom became synonymous with their idea of Africa. The two are intricately

attached so much so that they serve as a prerogative for Africa-as-freedom and

freedom-as-African.

The runaway

slave June Dey similarly comes from a tobacco plantation in Virginia, named

Emerson. His biological father is a slave from a neighbouring plantation who was

cheaply sold to the Emersons in the hope of saving the crumbling plantation capital

and helping it regain its former wealth and glory. We read that June Dey’s father,

June, killed the overseer in his last incarcerating place because that overseer

had killed his wife and baby. June is subsequently killed in Emerson because he

dared to defend his second family, the one he founded after arriving at Emerson

and from this union June Dey is born. June Dey’s biological mother, Charlottes,

occupies a mixed space between a domestic and field hand. During the day she

serves in the mansion but at night she sleeps in a shack with other field

slaves. She too was brutally murdered soon after getting rid of June. Their

baby christened Moses, was trusted to Darlene, a domestic slave and another

victim of the infamous system. Even when no one dared to divulge a single word

in respect to his father’s feats, June Dey or Moses truly stands to his

biblical sake name. The insurrectionary spirit becomes contagious and is

transferred from father to son nevertheless. He was raised as a domestic, but

when Mr Emersons decides to dispense with some slaves in order to raise funds

for a second nearby plantation that would plant cotton, June Dey leads the

insurrection that brings the Emerson plantation and its expansionist plans all down.

Indeed, we

read that the two June Dey and Norman Aragon are repatriated to Monrovia:

Norman because that was his mother’s dying wish but for June Dey the trip was

totally unplanned. After his spectacular fight against the masters of Emerson,

the opportunity presented itself as the runway June Dey is knocked out of

consciousness and finds himself in a ship, run by the famous American

Colonization Society (ACS) and is bound for Africa. All over the 1840s, the ACS

used to raise resources from the US Congress to secure the repatriation of both

free and freed Africans to Liberia. Meanwhile, the ACS established a footing

for US imperial planners during the heated race for colonies.

When

knowing that even Gbessa too had been in exile as she was excommunicated from

her village on the pretext of being cursed, the three characters conceive of

Africa less as a place of origin and more as a promise for greater, that is,

communal emancipation. This suggests how readers are invited to favour

ideological affiliation, not biological association. Indeed, Norman and June

Dey meet outside the Monrovia prison searching for ways of reaching Freetown

which is much of a mythical land and which involves how it is less a physical territory

and more of a life journey.

Why underlying

the symbolic meaning of the land? Lest Africa is fetishized, the simple act of

setting foot in Africa registers as just the beginning of the journey, the

commencement of the arduous work, neither an end in itself nor a call for passive

resignation. Moore’s vision for Africa serves the facilitation of encountering

like-minded individuals to unite the efforts and beat up against intruders for

collective and communal emancipation. Encountering Gbessa when she is literally

on the verge of death (she has been beaten by a snake), Norman has been at that

point looking for a medicinal herb (significantly, a living root—not one that

is cut) to attend to June Dey’s terrible stomachache. Instead of caring for

one, Norman has now to attend to two patients whom he barely knows. He could

have simply abandoned them to their fate and carried out his journey alone. But

he realized that a journey is meaningless without companions and fellow

travellers. Once this initial task of caring for the physical well-being of

committed Africans is successfully carried out, facing intruders both local and

foreign is next on the agenda. The three face French soldiers as the latter are

burning villages and driving the inhabitants into the slave market. Unparalleled

feats of success are achieved as Norman and June Dey save the villagers and they

all eventually mount a rebellion against the French enslavers. Historically, France

was a latecomer in the slave trade and France grudgingly abolished slavery as

late as 1848. French enslavers take Gbessa a prisoner; later, she is stabbed

and is left bleeding. But Gbessa’s curse specifies that she cannot die. She

stands for the undying spirit of insurrection, which explains why soon enough,

we meet Gbessa in Mr Johnson’s mansion, taken care of by Maisy, a servant. Understandably,

Mr Johnson plays a prominent role in the young and independent republic of Liberia.

By then, the

narrative may look like it slides into insignificant preoccupations: Gbessa’s

marriage with a prominent army lieutenant, Gerald Tubman, in the then newly

founded Liberian army. The union starts as a marriage of convenience but

eventually becomes rotating around love. The new elites of settlers badly

desire peace. How else to achieve that peace and trust with the unruly tribes

of the interior except through a marriage with Gbessa? The union stands as a

pledge, not a testimony, that Liberia will hopefully remain a single and

functional entity. June Dey and Norman are now mixing with the crowds. But the

mixed marriage should not lend a superficial reading of the novel. Already,

readers notice that within early Liberian high society, composed of individuals

who themselves had been slaves or had experienced slavery at a close range in pre-civil

war America have themselves resorted, however indirectly, to enslaving

practices in the form of wage labour.

Maisy’s fate,

when closely considered, speaks volumes. Kidnapped is one of the last enslaving

raids, her entire tribe was annihilated. As a sole survivor, she is now a

servant of Mr Johnson. The latter is presumably a popular leader of the young

nation but in fact he is the spokesperson of the settlers, those now powerful

people repatriated by the ACS. In a dialogue between prominent ladies, Miss.

Ernestine raises the remark that in being a house servant Maisy brings unhappy

reminiscences regarding the fate of domestic slaves on plantations in the

antebellum United States. The snide remark is swiftly answered with a tinge of

irony where Mrs Johnson points at the rumours which circulate how Miss. Ernestine

could be abusing the native inhabitants in her coffee plantations, treating

them like field slaves, implying that she perhaps should mind her own business

before attending to others.

The conversation

between the ladies, however calm in tone and seemingly casual, even friendly, remains eye-opening. What cannot be missed, however, is how these early founders of the

Republic of Liberia were not only conscious of the cultural divisions between

the inhabitants but were also aware of the long-term consequences of these

divisions. The bombastic and celebrations attitudes of starting a social order that

promises to be a rupture with the practices of the past and its institutions,

such as slavery, is now increasingly challenged. The ladies, as the exchange

illustrates, are in no way fooled by the promises of new or egalitarian beginnings,

allowing us to fundamentally question the chances of new beginnings or how the

idea of new beginnings serves as a strategy to fool idiots and simpletons. Engrossed

in their thriving businesses, the founding elites were aware that they were

leaving behind other social actors and that marginalization would be a

time-bomb, which if not immediately addressed, social unrest and even generalized

instability will transpire into the future. Nevertheless, each selfishly clanged

to short term interests and business calculations. Interests and calculations turned

out in the long run to be costly miscalculations.

The natives,

non-educated members of the interior tribes, were treated by returnees from

Jamaica, the US and other places (who were mostly enslaved) as second-class

citizens. Reading the history of coups in Liberia, it is these two social players

that constantly seek to undo and cancel each other. Even in the civil war that

pushed the author’s own parents to leave for the US, it was Charles Tylor ousting

Samuel Doe. The latter comes from the Krahn ethnic group, whereas Tylor is a

descendant of the socially upscale minority, a descendant of nineteenth-century

returnees from the US. The feud is more about who holds monopolies over-extraction licenses for foreign companies to mine gold and diamond. Still, the

feud is exacerbated by the historical divide that goes back to Liberia’s

unhappy foundation. This divide ushered in yet another cycle of violence and

looting for diamonds and other valuables. Both Tylor and Doe met with a violent

end and both were re-enacting the feud between on the one hand descendants of

former slaves, who to this day think themselves more entitled to rule since

they have been more civilized and on the other descendants of native inhabitants,

who excel in selling their credentials as the eternal victims of the

brain-washed former slaves!

This brings readers back to She Would be

King where lieutenant Gerald suggests at first and later instructs Gbessa not

to manually work in the farm, and to call for the help of the plenty servants

he is hiring so that she can lead a life of a lady. As the wife of a dignitary

in the young republic, he wants her only to supervise the workers simply

because Gbessa is now a society woman and her social manners should reflect the

social pomp of members of the high class. Any other Gbessa’s reaction, Gerald reasons,

reflects poorly on him, his social status as well as his chances of promotion. Naturally,

his eye lies on more prominent roles in the leadership of the young nation. In

his mind, he did not marry Gbessa to remain ‘stuck’ with a secondary role in

the army or administrating the barracks. Readers may evoke how Gbessa reacts: despite

the plentiful abundance of servants/slaves, she adamantly rejects and prefers

to carry out domestic duties, both indoors, in the garden and the adjacent

field, herself. Readers find out that Gbessa was particularly mindful not to charge

the numerous servants and workers with any task, domestic or otherwise. For

her, the practice however inadvertent summons slavery. No one can pretend that the

fresh memory of the inhuman practice is not overshadowing people’s everyday

interactions. Closely considered, the practice itself, not just its fresh

memory, casts its gloomy footprints on wage labour, rendering the latter anti-egalitarian.

Thus, wage labour sows the seeds of socio-political fragmentation and disharmony.

Bourgeois economics specifies that hiring aids and workers falls into the eternal norm of the division of labour where each individual works according to his or her skills set and fairly receives remuneration according to the tasks executed. Only the division of labour—through wage labour—found the basis of civilization, according to the same bourgeois theoreticians.

But in line with Karl Marx’s elaborations on the division of labour in The German Ideology (1848), Gbessa categorically rejects this commonsensical presupposition and deems it in service of justification, not an explanation. Indeed, the system of labour does not consider the worker’s actual coercion to grudgingly accept a wage in exchange for the task performed. In addition to seeking excellent and skilled performances, the division of labour primarily shuts means of independent subsistence, of that genuine aspiration of making a living without being forced to work for some boss or a hiring institution. Thus, wage labor, Gbessa reasons fuels inequality and sows seeds of generalized instability. Readers of the novel note how Gbessa’s soulmate, Safua, raises a rebellion against the leaders of the new republic because of the communal values which the wage system has been busily destroying. The Vai community–like several in the pre-colonial setting—cherish communal freedom. The Vai resisted the appropriation of their grazing lands and fiercely rejected domestication through wage labour. Now it is Safua’s son who is in charge of resistance.

Readers close reading Moore’s novel wherein Gbessa hopes against hope to stop the bloodbath, making sure not to pit the Vai against the settlers who are now the de facto rulers in Monrovia. Hence, the idea of Gbessa being king, as suggested in the title, should be taken as a pun: both a king and its negation, since Gbessa is a woman and the right expectation is rewarding her with the title of queen, not king, for active attempts to lift violence and foster the sense of citizenship among suspecting and uncooperative interior tribes. Indeed, Moore’s title squeezes her project as one that is radically egalitarian. In refusing to call the aid of workers and domestics, Gbessa rejects the title of king or queen. She views the title not only as the expression of an unearned or undeserved privilege but simply as the formalization of wage labour, the essence of slavery and disharmony.

Fouad Mami

Université

d’Adrar (Algeria)

ORCID iD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1590-8524